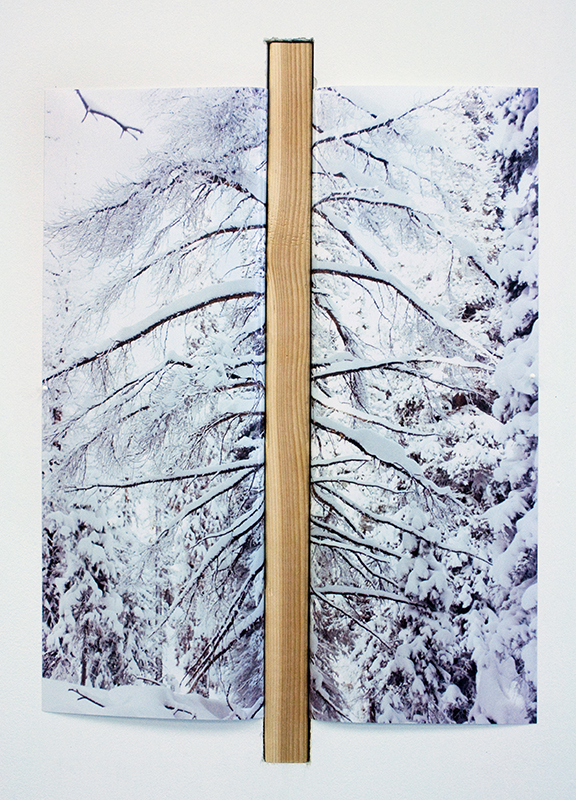

Letha Wilson's photo/sculpture mash-ups re-envision the American West.

Letha Wilson is an American artist who bends, smashes, cuts and folds her original photographs of landscapes and related subjects, like trees and rocks. Her ‘photo sculptures’, which incorporate lumber, steel and even concrete elements, challenge our impulse to categorize art practices and reinforce the materiality of photography, which has been obscured by digital processes. They layer art-historical references from landscape painting to Cubism in order to ask us: “what’s next?” Above all, Wilson seeks to bridge the gaps that keep us apart. She’s smashing our silos in the hopes of giving rise to something new.

Wilson’s work has been exhibited frequently since 2001, including exhibitions at Mixed Greens, Art in General, P.P.O.W., the International Center of Photography and the Studio Museum of Harlem (all New York), as well as galleries in Chicago, Los Angeles, Baltimore, Toronto and London, U.K. Here, Wilson speaks with curator and Magenta contributor Vanessa Nicholas about nostalgia, environmental readings of her work, and why there is a lot more to be said, photographically, about the American landscape.

Vanessa Nicholas (VB): Though your works are hybrids between photographs and sculptures, you’re primarily identified as a photographer. What is your formal training and how do you self-define?

Letha Wilson (LW): It’s only recently – within the last three to four years – that the photography world has embraced me. I still feel a bit uneasy about it because if I had to choose, I’d be considered a ‘sculptress’. That said, part of what I like is being both. I think in the studio as a sculptor, although I use photographs towards those ends. And, I actually was a painting major as an undergraduate at Syracuse University, and it allowed me much more freedom to the artwork I wanted to than, perhaps, as a photography major. The delineations within art schools, or at least the majority, divide the fine arts into categories that are not necessarily meaningful anymore. Also, the conversation pertaining to medium specificity is exactly what I am pushing. At the end of the day, I’m an artist.

VN: Was there a moment that propelled things forward for you? I mean, what precipitated your success as a practicing artist after school?

LW: For me, I think the shift in how my work was received happened as a result of people somehow finding my images on the Internet. The proliferation of blogs, Tumblr, and the way images are shared online changed how people discover artwork. I think that all happened around 2009 and 2010. Interestingly, I believe my work offers something that streaming images on your computer or iPhone cannot, which is a physical presence. They are almost all unique, they take up space, they are heavy, and they are best witnessed in person. Hopefully, to see the work makes you look again at a kind of image you might normally scroll through.

VN: Can you identify and elaborate on some early works that you consider key to your development as an artist? I’m particularly interested in what initially prompted you to bend, cut, smash, obscure and fold photographs, as it’s a seemingly irreverent treatment of the medium.

LW: In the beginning, I saw a lot of potential to push back or even break all the rules surrounding how a photograph is presented and treated. I thought it strange that photography galleries reserved a special section in the newspaper, even though to me photography was just another material or tool to be used for art-making. This seemed like fertile ground. Additionally, I was interested in photography as a potent emotional and mental trigger.

I have a notebook page from my studio – perhaps two years after grad school – titled: Ways to say ‘Fuck You’ to a photograph while still secretly adoring it. The list is made up of action items, like: arrows, bullets, push pins, obstruction, hole in, hole out, cover up and concrete. It’s a scribbled note that I recently unearthed as I realize it was really the beginning of that idea for me in the studio. This sort of love/hate relationship with the photograph continues. The irreverence and playfulness was something I had to work on and didn’t necessarily come naturally. I had to purposefully allow myself to make mistakes, play, fool around in the studio – and that took time. And, hey, I’m still at it!

VN: Oh my gosh, I love that. Can you tell me more about your studio and process? What is your working space like? And, how does a piece come to be?

LW: My studio usually has both ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’ areas, and it may go through phases when one or the other dominates. I’ve been going on artist residencies fairly regularly for the past five years, and I really enjoy the process of creating a studio from scratch in a new space. My studio is pretty small for what I am doing, so there is a constant reshuffling of tools and objects, and moving things back and forth. Sometimes I feel like I’m just continually making a big mess and cleaning it up. That’s also something that travelling does for me; it allows me to find a different head space and clear my mind, which is an important part of my process.

As far as how a piece comes to be, I am always working on several ideas and pieces at once, and everything is at various stages. Ideas for pieces I will make six months or a year from now are in the back of my head already. I store thoughts and they will come to fruition when the time is right. Or, maybe, one half of the puzzle is there, like an interest in a material; and then I’ll need to shoot the photograph that will compliment or complete that interest. Sometimes I use my contact sheets as a starting point or as a way to get the wheels turning. I have over 250 sheets of negatives shot with my medium-format camera. That’s my meat and potatoes. After I print the photographs, they come into the studio space and are treated poorly: cut wantonly, folded, ripped. But, sometimes, they’re folded quite delicately.

VN: Today, we consume images so passively. Your practice seems, in part, an honest, urgent and earnest attempt to reconnect with the magic of photography, to rediscover it. The importance of weight, space and physical touch are all counter to the digital tumult of images we’re fed on our devices. You touched on this before, but the way you describe your studio and process really reinforces this point for me.

LW: I absolutely agree. This may be another reason why there’s interest in my work at this time, when photography is in such proliferation, almost towards strangulation. But, people’s connection and reaction to photographic images still remains strong through the current.

VN: I see a nostalgia for early forms of photography in your work. That is, I see you reclaiming the materiality of early photo processes, like tintype or ambrotype, which produced unique images on plates of iron or glass. Does this resonate with you?

LW: This is true. Some of that comes from printing in a darkroom, and I also shoot with a medium format Yashica-Mat dual lens, which you could call an “old-fashioned” camera. More importantly, I relate to the scientific origins of photography. When I visited the Musée Nicéphore Niépce in Chalon-sur-Saône, France, where photography was invented, I was preoccupied with the fact that scientists, chemists and engineers figured out how to capture an image. This sense of scientific method, and the idea of the laboratory, both inform my approach in the studio: What if? What if I slather concrete on the back? What would happen if I pour it on the face? I keep a meticulous notebook now for all my ‘experiments’ that I always refer back to. I feel like I keep making discoveries that are taking me towards an unknown and, hopefully, never-to-be-reached endpoint. If my studio practice isn’t exciting and fun for me, then what’s the point?

VN: On a related note, you’re preoccupied with the American landscape, one of the oldest and most well-documented subjects of the photography tradition. What is there left to say about the American landscape? Why are you drawn to it?

LW: Ah, I would argue there is so much more to say! Its an amazing place. I mean, there are so many natural places in the world, but I am particularly drawn to the American West, where I grew up. Have you ever been to Utah or Wyoming?

VN: No, but I’d love to go.

LW: The scale and scope is just indescribable. It’s a real physical experience. The sense that you may indeed be the first person to step on a certain spot, perhaps four days into a week-long mountain backpack, is incredible and also humbling. We little humans are nothing in comparison and it puts things into perspective that is not found in our cities. Out there, Mother Nature rules and its tough. My family spends a lot of time hiking and camping, so I’ve been doing it my whole life. I am still touched by what I see every day out there. Its funny how the image of the West then feels so dated, and I wonder why. In the beginning, I was curious to articulate the contemporary landscape, and how to make the genre relevant and lift it out of cliché. In the end, there are so many types of photographs to be taken out there, and so many little spots to find. And light. And weather. Always changing. It’s so awesome.

VN: How often do you go out into nature to take photographs? Am I correct to presume that you’re camping with a camera? Do you go alone on these trips?

LW: I typically take one big trip every summer, and I also travel for artist residencies or through travel grants. I often have the pleasure of travelling with my mom and dad. Its great to combine a summer visit with them – they live in Northwest Colorado – with expeditions into the outdoors. Its actually what our family has done for recreation since I was little. My dad is really into outdoor activities, like the week-long family backpacking trips we made every summer starting when I was about ten-years-old, and rock hounding and ice fishing. My dad spends a lot of time just checking out places and exploring.

Sometimes I travel by myself, as well, which may sound romantic and exhilarating, but it’s usually more difficult for me. I am nervous about safety on my solo trips. My dad really drove home safety and caution in our family hikes. The reality of an excursion is way more pragmatic because it requires detailed planning and one needs to be safe, cautious and respectful in nature. It’s exhausting, intense, and filled with sun, bugs, cold and the elements. It’s not easy and romantic, but it’s worth it!

VN: I’m tempted to read your work politically. That’s particularly informed by an older project, Garden Gallery (Jasper Johns) from 2008, an outdoor planter that you made entirely from used walls and building materials reclaimed from art galleries for Waste Not, Want Not at Socrates Sculpture Park in Long Island City. Are you consciously incorporating environmental subtext into your work?

LW: I welcome the interpretation, and particularly as it relates to the recycled/reclaimed drywall series. Making that, I speaking to the glut of material produced by exhibition cycles and new iterations of a gallery space. Additionally, I have experience building walls for galleries and I’ve grown quite familiar with, if not fond of, drywall as a material. I wanted to defy people’s expectations of what that material should do. Asking why drywall shouldn’t be used outdoors parallels the other motivating questions we’ve already discussed, like, why can’t a photograph be cut and folded?

I believe the concern for the environment and nature comes from the heart of my experience spending time outdoors. It’s not something that I address overtly; but I allow the viewer to bring with them what they may and, perhaps, or ideally, they re-consider their own relationship or assumptions about nature.

VN: Can you tell me more about concrete/photo mash-ups? What is the relationship between those mediums for you?

LW: The concrete/photograph works have been an interesting experiment for me. I’m surprised by how these two materials work together. They came from one of my ‘what if’ moments. Bryce Canyon Cement Pour (2011) was the one of the first I poured. That piece is quite small, but it was the start. I often start with small ‘tests’ to see what happens. Then, accidents take it further. For instance, the glass breaks, and I like the way it looks without glass, etc. To me, this series resonates because, although the photograph represents a view of the natural world, a c-print is coated with plastic and created with chemicals, and the concrete is an urban and architectural signifier that is ultimately made up of this ground rock, ash. So, neither element falls safely into one category. They cross over and then come together. At the end of the day, they can even be purely about the colour and texture variants. Hey, they’re paintings!

VN: I love how your practice asks us to collapse categories, experiences and dimensions. It’s so freeing. Where do you look for inspiration? Who would you name as your artistic influences?

LW: Well, in the beginning and in grad school, I think Bruce Nauman, for sure. The way I think about breaking down an object or how you think about it relates to his early works. I’m also inspired by my peers working daily and what they do. Kate Steciw has been a good friend and colleague, a yin to my yang, artistically, I like to say.

I first heard about Kate when she reviewed a group show I was in back in 2010 for a photographer’s blog. Then, we were both in the BAM Next Wave show in 2011, and that’s when we first met in person. In that show, we were both given sort of carte blanche to make new work. I was amazed when I saw what she had come up with because, though it was so different in some ways, we were both interrogating the image and pushing it out of bounds. We both had what I would describe as a painter’s aesthetic.

I’m also influenced by Carolyn Salas and Stacy Fisher and Ethan Greenbaum and Amy Feldman. I also admire Mariah Robertson, Amanda Ross Ho, and Michael Heizer, and the grace of Anne Truitt’s work and writings, and the boldness of Jay DeFeo’s work – I could go on.

VN: Lastly, what are you working on right now?

LW: Well, it’s been busy. Coming up in November, I will have my second solo show at Higher Pictures in NYC, which I am excited about. I just opened a show in Paris recently at Galerie Christophe Gaillard. I have some other shows coming up in Milan and Amsterdam next year. Also, I finished my second artist book this summer, Between a Rock, which was published by Gottlund Verlag. The book format has been great as a way for me to work through ideas and images in a completely different way. It’s playful and also intimate. It’s fun to cut and fold and watch people interact with the books; it’s very tactile.

Letha Wilson’s solo exhibition at Higher Pictures in New York runs until December 20, 2014.

Vanessa Nicholas is a curator, community organizer and writer based in Toronto. She completed her MA History of Art at the Courtauld Institute of Art in 2008, and she now works as the Programs Coordinator for the OCAD U Student Gallery. She realizes independent projects as part of GalGalz.