Divya Mehra and the art of busting stereotypes.

Winnipeg-based Divya Mehra – who also splits her time between New York and Delhi – pursues a wide-ranging practice that embraces installation, sculpture, photography, text and, until recently, video. In her work, Mehra throws references to high culture and low, the East and the West, and the past and the present into a blender. The result is a shrewd mix of the personal and political that calls attention to issues around race, gender and identity, and how these are commodified by society.

Mehra’s work has been exhibited in solo and group exhibitions across Canada and the United States, and she is represented by Georgia Scherman Art Projects in Toronto. Here, she talks with curator and writer John G. Hampton about avoiding the “angry brown woman” label, working across mediums and how art can be like egg salad.

John G. Hampton (JH): I wanted to start this discussion by talking about introductions. As a female artist, a visible minority, and a member of the Indian diaspora, there is a tendency for viewers and critics to offer prefaces that place your practice within a culturally specific discourse. One of the more pleasurable – and potentially uncomfortable – things about your work is how deftly it preempts this tendency. It’s a difficult task to get in front of cultural expectations; since they are established long before any viewer encounters your work. So, I’m interested in how you negotiate that first impression.

Divya Mehra (DM): Well, John, we’ve just started and you’ve already gone and given everything away!

I grew up working in my parents’ Indian restaurant and with this came an ongoing series of questioning as I was perceived as some sort of “Brand Ambassador for India.” With each question about my superimposed pre-imagined arranged marriage, the gods I may have worshipped – blah, blah, blah – my frustration and resentment intensified. I think in a desperate need to avoid creating work that could too quickly be read, or is ‘too’ ethnic or gender-specific – although, most definitely, the work speaks to issues concerning those social constructs – I try to avoid any obvious indication of who is creating the work. This is, perhaps, most evident in the use of my materials today. I don’t think I could have reached this space until after I stopped making video work, where I was physically present in maybe 100 percent of the work.

Of course, a truly blind read is almost impossible. I’m not really sure if I ever (could) preempt the tendency to culturally frame my work before viewing. Placing the work within a ‘culturally specific discourse’ creates a ‘buffer zone’ for some, a space for explanation and justification, a reasoning out of my intentions and position: Oh, I get it, she’s just an angry brown woman. Although this may be a safe space for some, that biased view – a space devoid of invisibility – will always be a point of contention for me.

JH: In works like There are Greater Tragedies (2014), you seem to cross that line, becoming invisible as an author to the majority of the audience. Do you think about who you are to your viewer in that work? Do you think they read you as a generic “text artist” – white, male, pompous?

DM: That’s a pretty amazing description for a ‘generic text artist.’ I guess I saw myself as some sort of crazy pirate when we were mounting that flag to the roof of [Georgia Scherman’s] gallery. Just to be clear, I don’t want to be someone else (i.e., a ‘white male pompous’ artist). I just don’t want the dialogue to immediately travel into a space where my ethnicity is the first – and presumably only – topic of discussion.

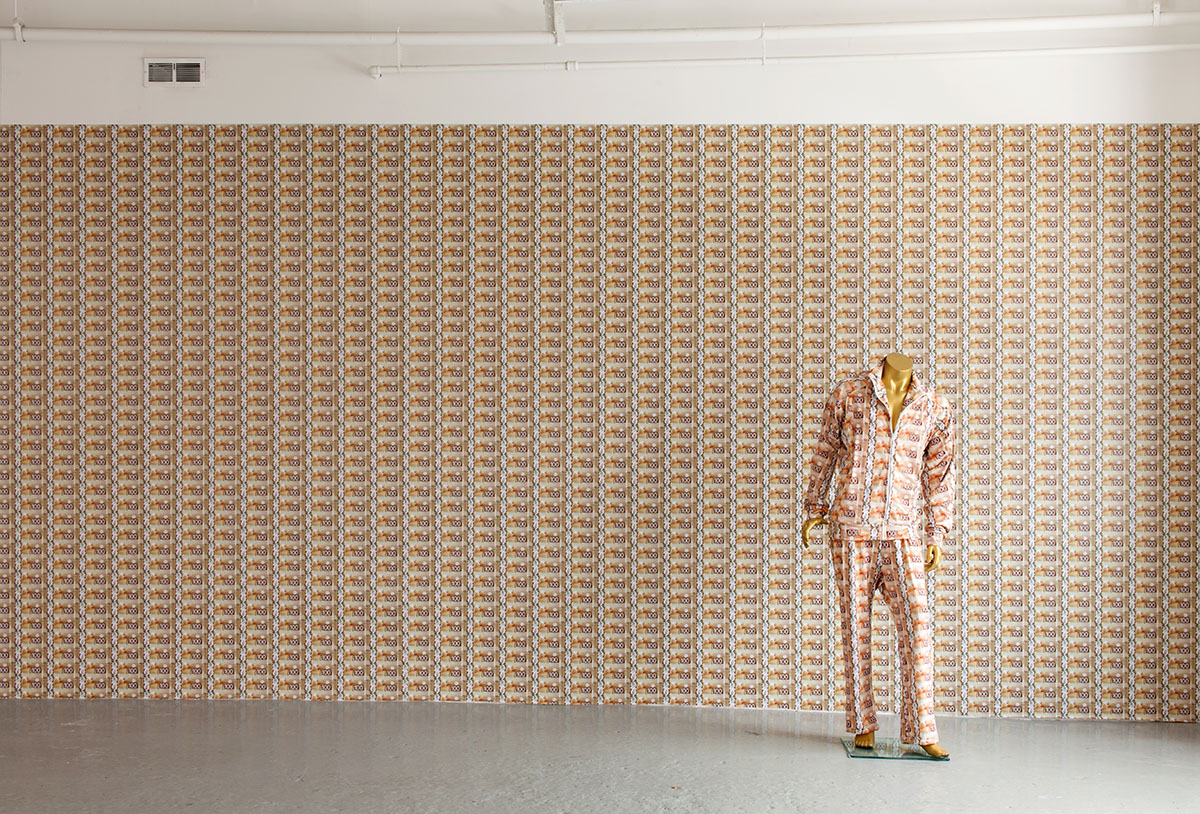

JH: When I first encountered Neutral Ethnicity (2014) – where you papered a wall of Georgia Sherman Projects with “specimens” of $100 bills on which a female scientist, who looked too “ethnic”, was notoriously replaced by a more “neutral” (i.e., white one) – it was exhibited alongside a tracksuit printed with the same $100 bill pattern. I was struck by how far removed the controversy surrounding that bill now seemed from our current cultural discourse. Jon Stewart once described topical humour as the “egg salad” of news, no matter how much care you put into making it, three days later no one is going to want to touch it. The same could be argued about art that deals with current affairs. By citing a recent, but not entirely current, piece of our cultural imagination, how does Neutral Ethnicity relate to the way we consume this kind of information?

DM: I wouldn’t see that work as simply ‘art that deals with current affairs’. That violent gesture, which I’m sure people don’t want us to see as violent, that erasure of the ‘ethnic looking’ woman, is the point of departure for Neutral Ethnicity. Whether or not I’m working with ‘rotten egg salad-issues’, I think we’re presented with, and consuming so much information at an incredibly accelerated pace that issues can become ‘piece[s] of our cultural imagination’ as opposed to a greater cultural discourse that must happen. I would hope – but there’s never a guarantee – that the work operates beyond a ‘current affair’. That it generates a critical dialogue around the circumstance: why did this happen and why was it acceptable? It’s disappointing when the work causes maybe just a smirk, and is quickly digested or digestible (delicious egg salad?), rather than pain and disgust at realizing the larger implications of those actions (rotten egg salad giving you some sort of food poisoning).

I am really into this egg salad analogy.

JH: I do like the idea of using your work as food poisoning for the viewer. I guess what intrigued me about that work is how it activated a recently forgotten memory of mine and made apparent just how disposable my political outrage can be. Beyond the issues of topicality in political statements, the aesthetic treatment of wealth in this piece brings to mind the gold Jaguar you mounted to the wall at Platform: centre for photographic + digital arts: I am the American Dream (still just a Paki), 2010. How do these two pieces articulate the differences in the ways in which “other” communities – and by this I mean culturally constructed images of otherness, as well as the diverse identities which are meant to be represented by those constructions – relate to money?

DM: It’s impossible for me to accurately articulate all the differences in display of capital and influence that may or may not occur in marginalized communities. However, these two works posture as ostentatious exhibitions of wealth and power, signs of nouveau riche for other communities. The concepts for both works originate in some idea of truth, which is then conflated with misrepresentations, and constructed identities of other communities.

JH: This confluence of varying levels of truth, generalization and misrepresentation seems to be a recurring theme in your work. In I’m going to talk about something very serious and I hope no one gets offended (sour grapes), 2012, the phrase “Aeropostale is fake as hell, Other Girls wear Aeropostale, therefore Other Girls are fake as hell” is printed on a gallery wall, white-on-white. This piece seems to be using the same type of rhetorical tactics that it is critiquing – a sort of ad hominem caricature of someone passing judgment on girls who wear Aeropostale that seems designed to paint the speaker as “fake as hell,” rather than – or in addition to – the girls who wear Aeropostale. Do you consciously keep track of, and direct, the multiple levels of contradictory rhetoric you employ in your work, or is it more organic than that?

DM: That text is a syllogism I wrote after watching a Zillion Dollar Chicks video on WorldStarHipHop.com.

JH: Ha! Do you think that question would have gone over better as a comment on a Zillion Dollar Chicks video?

DM: I’m pretty sure “The Supervisor” [a preteen girl from those videos] would have something to say to you.

JH: I guess what I was getting at was an admiration of the way you use language in such a circuitous and resonant way. This is probably most evident in your titles: fake political art (You’re good at making slogans), 2014, Contemporary South Asian Art (Conflicts of Perception/Oh hey she’s just too mainstream!), 2014, Set your lashes Free (Bad Criticism), 2012, and There are Greater Tragedies. What kind of relationship do you think the title has to the creation of meaning in your work?

DM: I appreciate that. I don’t usually write artist statements. I actively avoid them. I do, however, endlessly take notes in one master document. This document is made up of fragments of conversations, chopped musical lyrics and text from whatever I’m reading, and sometimes even dialogue from things that I may be ‘hate-watching’ online while pretending to work. When I’m in the middle of a project, I spend a lot of time with this nonsensical endless text document. It actually really informs the direction the work travels, functioning much like a sketchbook. So, it’s never really necessary that the works take any one particular form, as in I’m not committed to painting or sculpture, but that the final medium (like in the works that you’ve cited, vinyl, textile, photocopies, etc.) resonates with a larger public.

JH: So the title takes the place of your artist statement then?

DM: Yes.

JH: In your disavowal of having a commitment to any specific medium, it sounds like language is your primary medium even if it is in interaction with other mediums.

DM: Yeah, I guess it is. Having the space to endlessly transform text into jokes, syllogisms, one liners and aphorisms (among other things) that (often) oscillate between multiple languages is probably one of the more experimental and enjoyable aspects about my artistic practice. It’s in these spaces (text works such as There are Greater Tragedies, or Doomsday (Collective Failure) OR Death may be your dessert, 2014) that I briefly occupy some sort of autonomy.

A new neon text-based work by Mehra is on view in the “window” display space at the Artspace Building in Winnipeg until January 31, 2015. Mehra is also scheduled for a solo exhibition at the Confederation Centre for the Arts in Charlottetown later in 2015.

John G. Hampton is a Curator/Artist from Regina, SK. His recently curated exhibitions include Why Can’t Minimal: an exhibition of humorous minimalism, Coming to Terms: translation and the multiplicities of languages, Sculptural Video: video art beyond the screen, and solo exhibitions by Heather Cassils, Soft Turns, and Richard Ibghy & Marilou Lemmens. He currently lives in Toronto, ON, where he is the Artistic Director of Trinity Square Video and the Curator in Residence at the Justina M. Barnicke Gallery.