Rodney Graham and the aesthetics of break time.

Internationally recognized Vancouver-based artist Rodney Graham hardly needs an introduction. An accomplished writer, musician, painter, filmmaker and photographer, as well as a performance, sound and installation artist, Graham has mastered many disciplines, but is best known for his large-scale photographic light boxes. For the past two decades, he has assumed the guise of a wide range of characters in often humorous situations, posing in tableaux constructed within his studio.

Graham’s work has been exhibited throughout North America and Europe. In 1997, he represented Canada at the 47th Venice Biennale. In 2005, he was the subject of a major survey exhibition circulated by the Vancouver Art Gallery. Most recently, he has had solo exhibitions at the Art Institute of Chicago, Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona and the Jeu de Paume (Paris), and his work is held in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art (New York), the Centre Pompidou (Paris) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), among many others. Graham is represented by 303 Gallery (New York), Lisson Gallery (London) and Hauser & Wirth (Zürich).

The following interview took place in mid-May at Prefix ICA in Toronto, which is currently exhibiting three of Graham’s light boxes.

Xenia Benivolski (XB): Rodney, reading the exhibition essay that came with the show, I noticed it says that while your practice is interdisciplinary, you are still grounded in photography. I was wondering if you could speak to that statement.

Rodney Graham (RG): I think the work I do is still related to photography, but more as a kind of performance now. I technically don’t have a lot to do with the physical realization of the pictures except as a producer, within this funny vision of myself as an executive producer/actor. (I sometimes say, like Tom Cruise.) These works were produced in large format with the help of a photographer in Vancouver, Robert Kaiser and with my crew: Josh, Scott and Shannon. The image Basement Camera Shop, Circa 1937 (2011), for example, was produced from a found image – a snapshot that I bought at an antique store in Vancouver. I think it depicts a camera store somewhere in Manitoba. I reconstructed it, basically, by making a few interpretations to produce a work about snapshot photography, a basement snapshot. I don’t really consider myself a photographer. I’ve used the medium a lot in the past, and then kind of dropped out of it for the last year or two. I’m just starting to get back into it, digitally.

XB: You got a bit into painting, right?

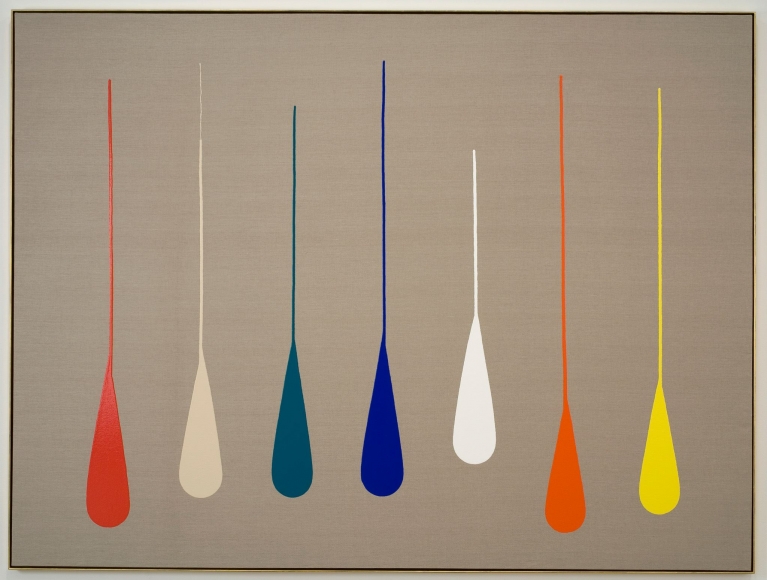

RG: I kept trying to integrate painting into my work by continuing to make paintings and sculpture to be used as props. It started with an idea for a piece about a guy who had just come back in 1962 from New York and had seen a Morris Louis exhibition. He’s kind of an upper-middle-class guy, maybe a doctor or something, who became suddenly interested in art later in life and started to experiment with painting. Drip painting in his living room or something like that. So, I began by made a bunch of drip paintings for it and I ended up making more and, you know, generated a body of work. A lot of it: I mean a lot of paintings. I made hundreds of them.

XB: Impressive.

RG: But, back to Morris Louis. In his last days, he was working, he was still inspired, and he made his paintings at home. Do you know the story? He made them at home in his kitchen, these very large paintings, and the space where he was working was much smaller than the paintings themselves. He’d have to roll them, but he made hundreds of them, so I kind of used that story to generate the idea. I didn’t really plan on that because I didn’t know if they would be interesting to me as artworks. Around that time, I was experimenting with looking at other kinds of painting from various historical eras: School of Paris, paintings in the 50s, something that I missed in my own education. Or, not so much my own education, but my own evolution as an artist. I never went through that so I did it later.

XB: How so?

RG: Going through a change of pace. I tried to learn painting, almost like a student, and I still do that. Recently, I made a piece that I haven’t exhibited yet called Artist in Artist’s bar. It’s a bar set in the ’50s, possibly in New York or Toronto, an image of a guy just sitting in a bar and the walls are filled with abstract paintings, evidently made by a group of people who had come in and traded the work for food and such. So, I made about 18 paintings for that, and I continue to make prop paintings. So, when I show it, I should have some additional hypothetical paintings.

XB: Can we talk about the way hypothetical artwork enters the image of the studio in Pipe Cleaner Artist, Amalfi ’61?

RG: Pipe Cleaner Artist is based on a Man Ray photograph of Jean Cocteau making little pipe cleaner constructions like the ones in the film Blood of a Poet (1930). Sometimes they’re just called wire sculptures, but I’m quite certain they were made of pipe cleaners, a craft material that I remember using as a kid. I got a bunch of these pipe cleaners mostly from head shops in Vancouver, they have craft ones now that kids use, but these are the real old school ones. And so, I wanted to make this work about an artist in his studio, you know, maybe someone working under the influence of the informality of a particular period in the 1960s or ’70s. And then, I saw this photo of an artist studio in the ’60s, in the mountains in Italy: it was a ceramic studio, and I’ve replicated it as closely as possible, placing him in a reverse pose. In the original photograph, the artist is sitting on the other side, and he’s working on a painting on the floor. But, the studio is similar and the art on the walls is hypothetical. But the studio, the window and everything is right out of this photograph.

XB: I’m interested in the description ‘pipe cleaner artist’ in regards to the way people self-describe as ‘web artist’ or ‘food artist’ and so on. I always found the direct material-as-medium designation very strange, both grammatically and otherwise. So, coming back to the exhibition essay where it talks about how these works punctuate a difference between the amateur and the master, I was wondering if there was a intended thread regarding a classical proto-Marxist idea around the dynamic between intellectual labour and physical labour in art production, playing out in a class sense, and in photography especially, since you mentioned you no longer physically produce the photographs, but work more so in the realm of ideas.

RG: Well, I wasn’t consciously thinking about a particular issue. I was thinking of a person, maybe an American artist after the war, staying in Italy, considering this idea of utopia, a former bar converted to a rustic studio, something I’ve never had or experienced. I’m just getting back to an interest in the idea of a studio. Ian Wallace and Jeff Wall back in Vancouver would have studios because they painted before they became interested in photography, and I’ve never had that, so I’m now becoming fascinated with this idea of a studio practice, an idea that lands in a certain conceptual era, where I find myself not having a studio. I don’t need one, since I have my works fabricated by somebody else. So, this reference to a pipe cleaner craft project was also something super simple and repetitive, kind of a blissful activity.

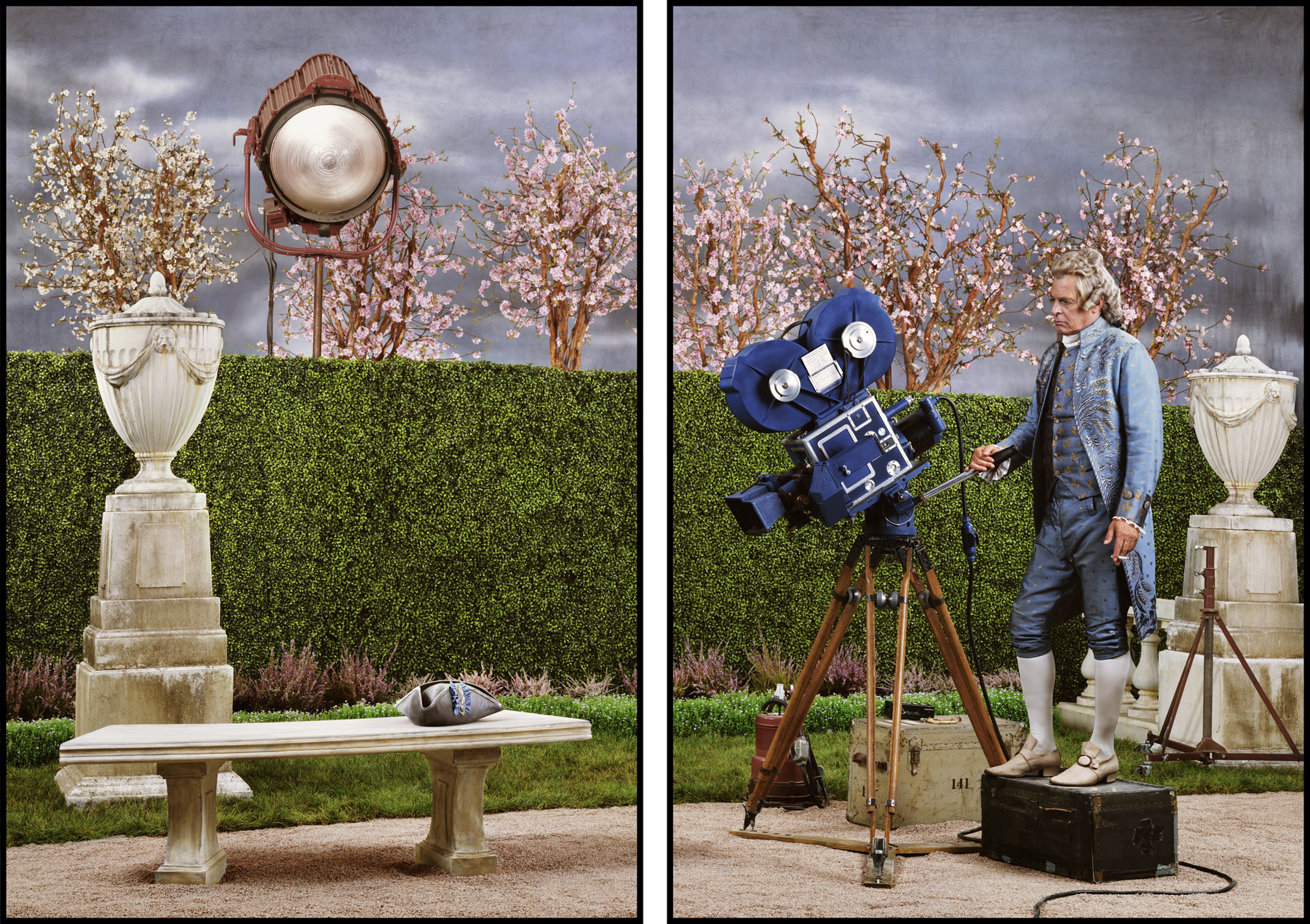

XB: So Actor/Director, 1954 (2013) speaks more about this sort of artist-as-producer methodology?

RG: Yeah. Well, this is also inspired by a photograph, by Erich Von Stroheim. In his films, he often played these really intense military men and, of course, he’s a director, too. There’s this photograph of him behind the camera, wearing a period costume that he’d been acting in because he was the star, he was an actor-director. So, this piece kind of became a little bit about myself in that sense. I’m not really a director in my own images, I’m more of a producer, so I’m giving instructions to people who are directing me.

This piece is part of a series about smoking, called Four Seasons, and this is ‘Spring’. I really had no intention of making this series about smoking, but I once made this piece called Betula Pendula Fastigiata (Sous Chef on Smoke Break), 2011 that pictures a sous chef in a white costume, with a hat and everything, sitting under a tree in a park, smoking a cigarette. And ,I was thinking of all these people taking smoke breaks: People in the service industry and such. I saw a guy sitting in front of a hedge behind a restaurant having a cigarette and I thought about making a piece about nature and smoking. And also, just you know, I like the idea of being not a chef but a sous chef, you know – not really a chef, but someone who is old enough and should be a chef ….

XB: Like it has the word chef in it, but its not.

RG: Yeah, and anyway, sitting under this tree in a smock that says ‘Seasons’ because, in fact, there’s a restaurant in Vancouver called Seasons in the Park, a nice ‘public-park-restaurant’ kind of restaurant where old people go. I liked the idea of people outside a restaurant, in a park, haying a smoke under a tree in this sort of idyllic setting, taking a break. Once I made that piece, I decided to make another one called Smoke Break 2: Drywall. That one was set against a piece of drywall recently being done so it’s patched and it looks a bit like snowflakes, and there’s a heater. So, a friend suggested I should do the ‘four seasons of smoking’ so Drywall was ‘Winter’, and the other one was in the summer. The next one in that series was a work that I had always wanted to do. It’s based on a painting by Thomas Eakins, Max Schmitt in a Single Scull (1871), a classic American-realist masterpiece. I made a very large three-panel work where I’m in a kayak looking at the camera and there’s an industrial bridge behind me. But, I’m not smoking. I thought, ‘Well, you know, this guy wouldn’t smoke. Or, maybe he’s a smoker, but he’s not smoking right now.’

And then, I had ‘Spring’ to do. I thought, I’ll do this scene from a film somewhere in the 50s, set in Paris in the spring in the 18th Century, with this guy just taking a break, acting and directing. I was also thinking about this film I really like called Monsieur Beaucaire (1924).

XB: I feel like all three pieces at Prefix connect in a funny way around this tension between labour and leisure. Is that something that you consider in your work?

RG: Yes, there definitely is a thread about leisure this idea of break: he’s just on this set, having a smoke, thinking about this simple shot. And, I guess in the Pipe Cleaner Artist as well. In Basement Camera Shop there’s also a person working.

XB: Since you’ve been making work for about 40 years, could you reflect on your motivations and if they’ve changed?

RG: It’s not exactly the same. I have more of a motivation towards making commercial work, making a living. When I first started , I wasn’t too worried about that because life was easier then.

XB: In Canada, or in general?

RG: Well, in general it was easier to live if you didn’t have to deal with these complications around having a studio. So, I didn’t worry about making a lot of space for the work: now that I do have to think about that, it’s different.

XB: Has your focus shifted conceptually?

RG: Earlier, I was doing a lot of conceptual text-based work, but then I wanted to make something that had less of a back story, something a little more accessible: you know, obviously it works, the back story I’ve been telling you, but it’s not a context. Sure, there are citations that are important, but maybe you don’t directly need those citations to understand this work, to be able to have some kind of response to the picture. So, I moved in that direction, which is to say, it makes it a bit more popular, I suppose, in the sense of accessibility. Before, I was making more rarefied conceptual work that needed a lot of intellectual support. I’ve rejected that a little bit.

XB: When do you think this happened?

RG: I guess in the ’90s, maybe at the end of the ’80s. In the early ’80s, I was still doing more conceptual work. When I started doing large format photography, I began trying to make things simpler, and that really accelerated when I made the film Vexation Island (1997), for the Venice Biennial. That film piece was really ripping on Hollywood tropes and cliches. So, my earliest works were conceptual photography, Polaroids and such: working with very basic elements of photography, and the film works kind of came out of that.

XB: When you were talking about the Artist’s Bar, I was thinking about Vera Frenkel’s …from the Transit Bar (1992) and wondering why so many lens-based artists end up working with this idea of a kind of space that can be anywhere and what these spaces facilitate.

RG: Well, for me, it was about this idea of an artist bar or hotel where there is the tradition of a direct exchange of art for food, which is something I’ve done. I was interested in that economy, which is kind of another art world. It comes out of my own experience of trading, and it’s super common. Artists who don’t necessarily commercially sell are engaging in this milieu, the artist’s milieu.

XB: So a little bit back to that subject of economy and leisure.

RG: Yeah, it’s about different kinds of exchange.

Jack of All Trades, a solo exhibition of works by Rodney Graham, curated by Scott McLeod at Prefix ICA in Toronto, runs until July 30, 2016. It is presented in conjunction with the Scotiabank CONTACT Photography festival.

Xenia Benivolski is a writer and curator currently based in Toronto, where she co-runs the 811 gallery and the NoYo AIR program.