Toronto-based Jen Aitken creates floor-based sculptures out of concrete that recall Brutalist architecture; like Marcel Breuer’s iconic building that once housed the Whitney Museum, Aitken’s sculptures manage to feel sturdy and precarious at the same time. Drawing from a series of recurring forms that she casts and assembles herself, her sculptures are like puzzles that invite viewers to circle them to determine the logic of their construction. There is nothing flashy about Aitken’s sculptures, but spending time in their understated presence brings visual reward, especially when one gets up-close to their textured, subtly colour-flecked surfaces. The phrase ‘less is more’ certainly applies to Aitken’s work.

Aitken received her MFA in 2014 from the University of Guelph, and her BFA in 2010 from Emily Carr University. Her work has been seen in group shows at Diaz Contemporary (Toronto), Kamloops Art Gallery (Kamloops), and Hamilton Artists Inc (Hamilton). Magenta editor Bill Clarke visited with the artist at her live-work space in Toronto’s West End as she was preparing for her first solo exhibition in Montreal at Battat Contemporary.

My studio is in my apartment, so I’m always battling with dust and mess. You’re here on a really clean day. But, I really appreciate the intimacy this set-up gives me with my work. There’s always a part of my mind that’s focused on my work, even if it’s unconscious or peripheral.

The new sculptures for my show at Battat, called Numa, are all made up of two or three individual concrete units that stack or interlock together. They evolve one unit at a time. The first unit is the most difficult to determine, and then each additional unit is a response or a solution to the one that came before it. So, the final forms aren’t predetermined at all. I begin each new sculpture with a vague sense of its particular formal characteristics: something hovering on the ground and spreading outward, for instance, or something folding in on itself and cupping an internal space. I then start figuring out the first unit, constructing a number of full-scale paper maquettes until I arrive at a form that holds my attention. It also has to behave differently than my previous sculptures. I don’t want to repeat myself. After I’ve sat with the maquette for several days and I still want to realize it, I make a mold out of wood, plastic and foam. Concrete will pick up the texture of whatever surface its cast against, so I decide ahead of time which textures I want on each side of the concrete form, and build the mold accordingly. I never do any buffing or other finishing work on my sculptures, it’s important that their surfaces are intrinsic, not applied.

These are some pieces of wood, plastic and foam that I use in my molds. I work with a restricted set of shapes, so I can often reuse various pieces of material several times without having to re-cut them. For the past three years, I’ve been designing forms within a fixed set of limitations: ninety- and forty-five-degree angles and correlated radii. This consistent vocabulary unites my sculptures together, so that they accumulate meaning as a group. The familiarity of my terms also grounds my work in the everyday built environment, which offers multiple entry points for the viewer — my sculptures almost look like a lot of things you know (furniture, infrastructure, etc). But the forms keep changing and unfolding as you walk around them, so they resist being pinned down.

In the past year, I’ve become more interested in the negative spaces within and around the sculptures. My earlier works, in the series titled Poda, were quite contained, even monolithic, and I’ve been working to open my forms up. My new sculptures really eat into the space that surrounds them.

My sculptures are really about getting you to move around them, seeing their forms and spaces shift in relation to your own movement. Their scale and proportions are also in direct relation to your body. Of course they’re not meant to be actually interactive, but they suggest to you various contorted ways of sitting or folding over. I also try to work against my own sense of a sculpture’s front or back, though there might be a side that I want viewers to encounter first. I want to control the pacing of the form, in a sense, to make it seem solid at first, and then open up over time, for example. I’m always excited to see and move around my work in a gallery space. It always looks drastically different than it does in my studio.

I started working with concrete because I saw it as both absurd and practical. Absurd because it’s heavy, messy, labor-intensive and virtually impossible to manipulate once it’s cast. Practical because it’s cheap, readily available, and quite forgiving to work with in its liquid state. I also appreciate its range of applications and associations—from the dome of the Pantheon to the botched patch job on your neighbour’s front steps. Plaster and other casting materials are more specific to sculpture.

I use pre-mixed concrete from the hardware store, but sometimes add extra cement to get a smoother consistency and darken its tone. I often add powdered pigment to the concrete mixture, to give the grey a slight yellow or purple undertone, for instance. These variables, along with the different textures I mentioned earlier, really expand the range of the singular material.

The concrete takes seven days to cure, so when I’m finally de-molding a piece I’m really seeing it with fresh eyes. Because it is such a long and messy process, I work on several pieces at once.

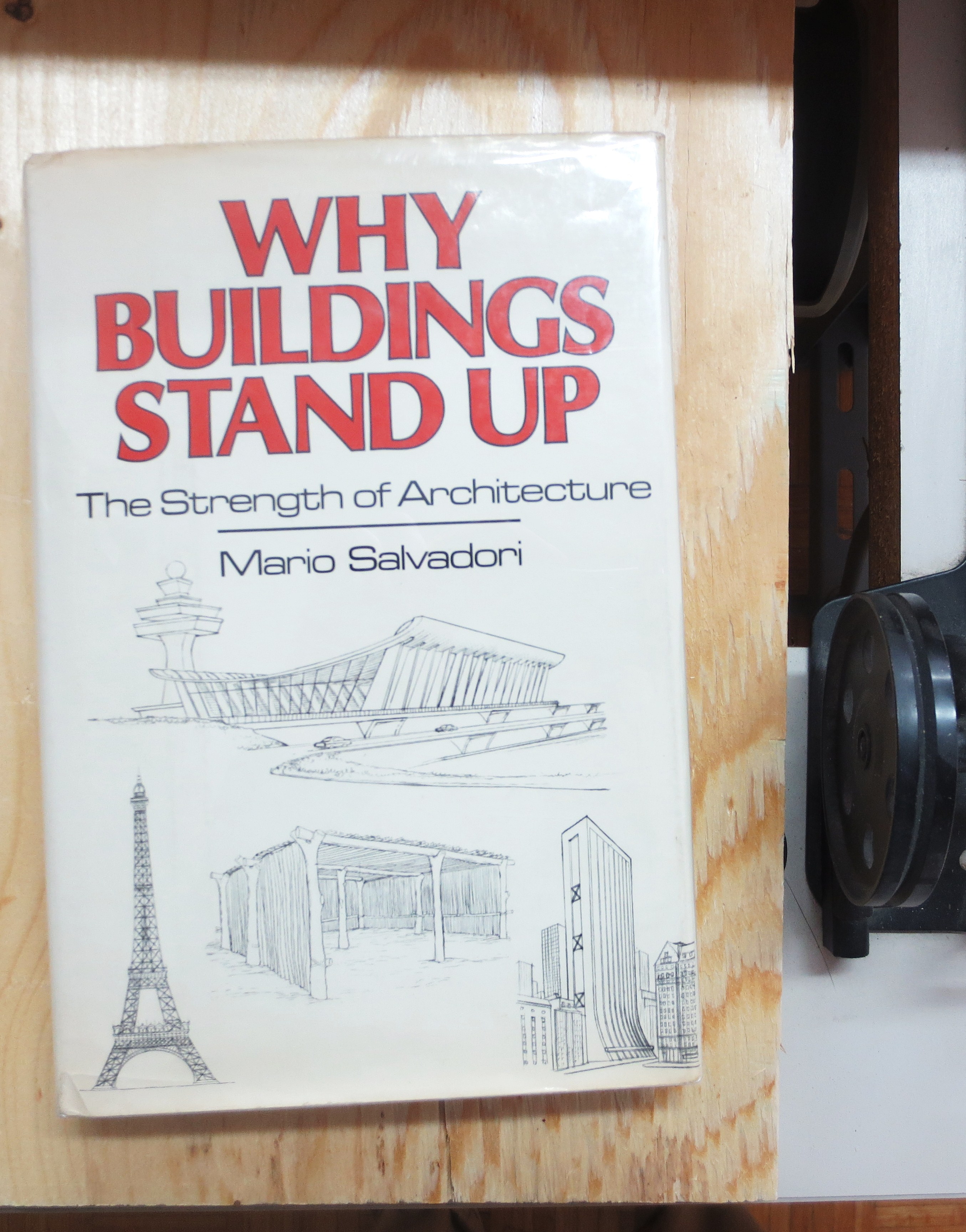

I think you found the only book I have lying around! Most of my research is observational and material. My work is really about pushing language out of the way and resisting the urge we all have to interpret everything. I keep my books away so as not to clutter my thinking. This book, however, is interesting as it’s a history of architecture as structure, rather than as style or form. It starts, for example, with an account of how the Egyptians figured out how steep they could build a pyramid before it buckled. My new work involves a lot of balancing and counterbalancing. The individual units aren’t fastened together, but simply stacked on top of one another. I want to use gravity as another one of my parameters to push against. The top block of my sculpture called Lunopel, for example, secures the middle block that cantilevers out from the core axis of the sculpture. The forms and negative spaces in my work are fairly complex and pictorial, so it’s important that they’re anchored by a clear and rudimentary structure.

This is the top surface of Galomindt, and you can see the wood grain here. This form was dyed black, the darkest of the group, and also picked up a little yellow from the plywood. I always add small pieces of polyurethane foam to my concrete mixture, like an aggregate, which you can see poking through the surface here. I use a two-part liquid foam so that I can dye it the colour I want. Then when some pieces inevitably show through, they look like painterly marks, but they’ve come from the inside out. They also have a tip-of-the-iceberg effect, making you conscious of the fact that you can only see the surface of the form, and can’t access its core. Adding foam also has the practical benefit of taking about twenty or fifty pounds off the total weight of each sculpture. I think every decision should be both poetic and pragmatic.

These are some of the shipping crates for the work in the show at Battat. I make specific boxes for each concrete unit, so that they can be rotated 360 degrees without causing any damage. On the left is a painting by my great-grandfather. He died before I was born, but his strong presence carried on in my family. I grew up in the house that he had built for his family, where my grandmother grew up, and it was full of fantastic remnants of his life there as a restless maker.

Jen Aitken’s solo exhibition continues at Battat Contemporary in Montreal until June 25, 2016. She also has solo exhibitions scheduled for September 2016 at Centre Clark in Montreal and Spring 2017 at YYZ Artists Outlet in Toronto.

Bill Clarke was the Executive Editor of Magenta Magazine Online from its inception in September 2009 until May 2017. His writing has been published in Modern Painters, Art Review, Canadian Art, Artnews and several other publications. In January 2017, he assumed the position of associate director at Angell Gallery in Toronto.