Navigating politics, photography and collage with Jp King

The trans-disciplinary media artist Jp King is a renaissance man, wearing multiple (paper) hats. As a scholar, King is helming what he terms his “practice-led research” at OCAD University, where he’s completing an MA.

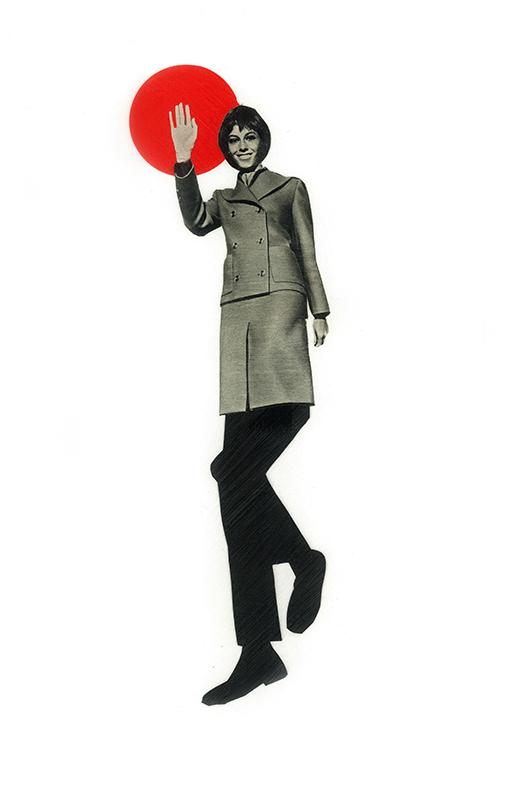

He’s a designer and editor at Papirmass (directed by his wife and collaborator, Kirsten McCrea); a collage artist of quickly growing repute – he’s recently exhibited at the Art Gallery of York University, XPACE, Whippersnapper Gallery, and the Klondike Institute of Arts and Culture; and his collages have been featured in publications such as Uppercase, Fast Company, Carousel, Penguin UK and, most recently, Collage: Contemporary Artists Hunt and Gather, Cut and Paste, Mash Up and Transform, published by Chronicle Books; and he operates the publishing lab Paper Pusher, which specializes in experimental Risograph printing and design, and is fast becoming one of Toronto’s most in-demand publishing houses and a platform for forward-thinking collaboration.

At the center of all this stands an articulate and conscientious artist straddling complicated arenas, and softening their lines. Between print culture, publishing and collage – in addition to performative and socially engaged exhibitions that read like a bygone era embodying ideas from the future – King is building a profile of mutable savvy and a practice bearing material warmth.

In this conversation with art writer, editor and publisher Sky Goodden, King focuses on his role of collage artist, especially in a moment of its increasing popularity. He discusses issues inherent to the medium such as its historic association with politics; new to the cause (i.e., how can collage art navigate a market overridden by more traditional media?); and unique to his own practice – one too various and manifold to be defined in pairs.

Sky Goodden (SG): There is a demonstrable resurgence of interest in collage media, particularly among a younger generation of Canadian artists. I wanted to talk about that with regards to your timeline. How do you situate yourself in relation to this medium’s popularity? Were you aware of it before you began?

Jp King (JK): As I see it, collage has really existed as a forefront technique in art since the dawn of modernism. To suggest that there is an immediate resurgence of any kind, I think it’s just a slice of the moment. I’ve been working in collage since 2006, and I’m not sure how to contextualize that within the current trend.

I look at contemporary drawing practice now, however, and see such an enormous diversity. And, I think at the time when I began, I was really close-minded to trying to achieve realism. That might be in part because both of my parents were photographers. They were re-producing reality with their own creative twists, of course, but with the snap of a button they could do what I saw in my mind.

SG: In a piece you wrote for Kolaj Magazine, you make an argument for collage that addresses the overpopulation of images. It was written with a severity I took to be facetious, but threatening some truth, as well. How do you regard this issue, really? Are collage artists addressing an oversaturated world of images? Are they not just adding more?

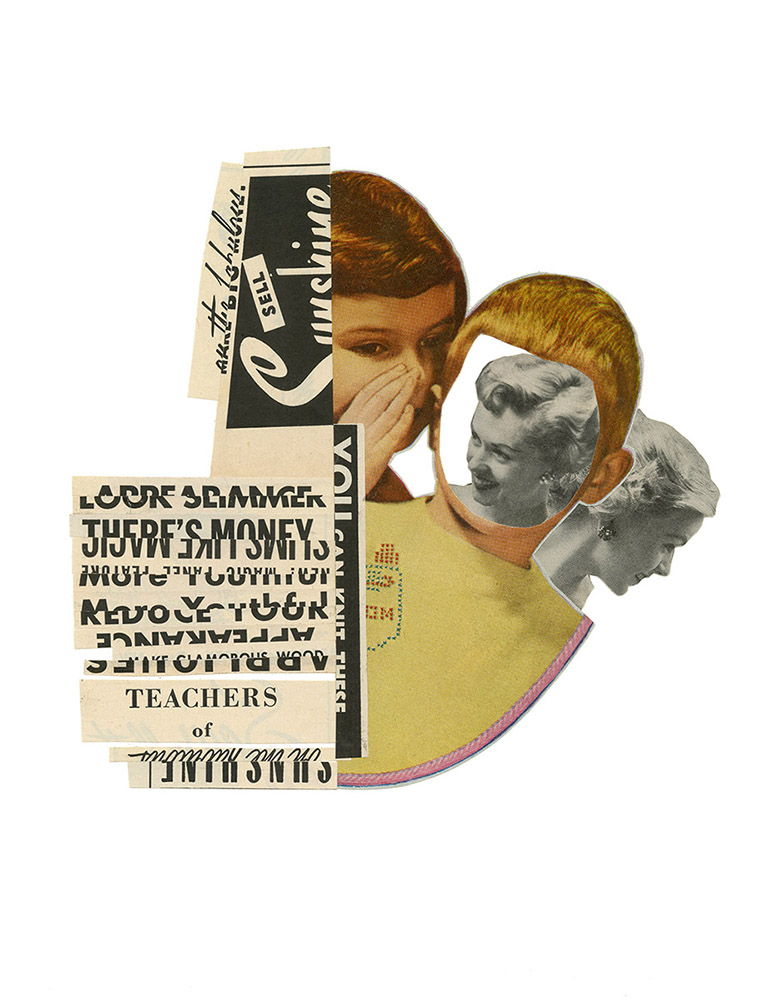

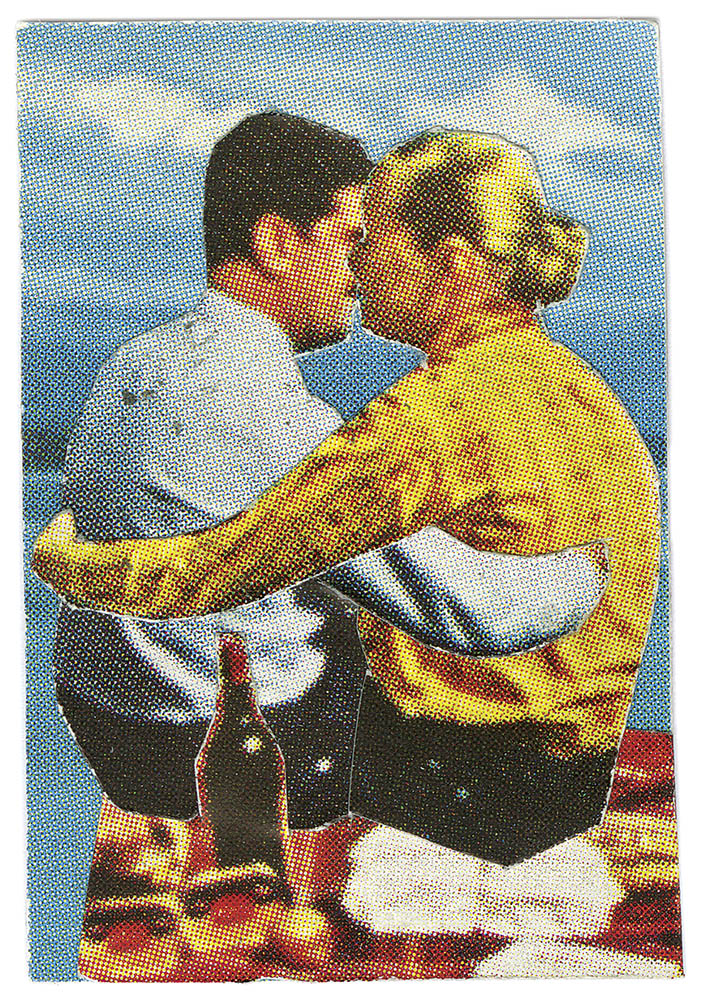

JK: I’ll start by saying that I believe all artists use some techniques of borrowing and appropriation. To take scissors or a knife to a page is just a bit more of an honest approach to what is otherwise prevalent. I think in big part, that comment [I made] was in reaction to the glut of advertising, as well as being raised in a family of image-makers. What’s odd is there was a time when image-making was far more precious. Photography was restricted to film, for instance; it was resource-intensive. You could only carry so many available pictures with you. Moving into the digital age, there’s suddenly an endless proliferation. To turn back to the printed image as some type of sacred being, but to perform some kind of sacrilegious surgery on it, is enormously pleasing for me. And, I think, quite liberating.

SG: Where does that impulse come from? It is advantageous? Possessive? Destructive?

JK: Well, I do have a real fascination with waste and excess. which I’ve come to realize is inherently tied into destruction. To be surrounded by so much, and the ability to intentionally deteriorate it, is sort of like a privileged narcissism, in a way. But, that said, I think there’s also a re-negotiation of the domain of ownership, which is to say that anything publicly accessible sort of belongs to me – a totally entitled approach.

SG: Not one unusual to our generation, though.

JK: No, that’s right. But, it’s not a motivation I’m particularly aware of… that entitlement. I think that sort of liberation comes out of a pure joy of availability. There is so much there, I’m a kid in the candy store. And, it doesn’t seem as though there are rules anymore.

SG: You were asked in another interview about your education in creative writing, and asked if you saw yourself perpetuating new narratives in collage. You said “not so much.” When you begin a collage, though, are you not envisioning an image (if not of a narrative) in your mind that you’re looking to materialize on the page?

JK: I’ll say that at the time of that previous comment, about four years ago, I think I saw a much greater distinction between my writing and my art. I’m coming to see all of it fusing together. I think now that I approach all images with the knowledge that there is an inherent narrative. My play as a collage artist is the erasure of that origin narrative, and the re-creation, repurposing of materials, toward something new.

SG: Like the Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) by Rauschenberg.

JK: Yes, that’s one of my favourite works. That stands out in my mind. I think that in trying to claim some artistic territory for my own that I saw photographs as fertile territory for narrative appropriation. I watched my parents tell stories through pictures.

SG: Photographs can be quite elusive in that regard, though.

JK: No, they weren’t scientifically objective photographs. I wasn’t raised in that environment. But, isolating and re-contextualizing elements [from photographs] brought about new potential for me. And, in many ways, the form of collage constituted by cut magazines, vintage paper and glue is really just one material manifestation of collage in my life, in my practice, and everything else I do.

SG: Thinking about the history of the medium, 20th Century collage has largely been used for political purposes. Where are politics in the medium today, and how much do you reflect on the legacy you’re building on and contributing to, in terms of its political vantage?

JK: Well, I’ve always found ‘politics’ to be a tricky term, because I feel immediately that it carries the soap-opera of regional activity that I can’t stand. On the other hand, I do think my work through-and-through is sociologically conscious and ideologically based. It works towards a vision of a better life, a greater society and community. Historically situated, you can look at the work of John Heartfield, who very intentionally juxtaposed Hitler’s face in compromising situations and was able to deliver a political message. On the other hand, you look at the more absurdist-driven work. For example, Tristan Tzara pulling words out of a hat to create a poem, and the ensuing riot that comes from a grab-bag of his non sequiturs. So, I see myself definitely as politically-situated, but more in the Tzara tradition, and less so the Heartfield one.

But chance only goes so far to disrupt politics. We’re in a position where so many images have been made, and where advertising has co-opted so much artistic language that it’s pretty difficult to make images that truly carry an inherent political meaning [anymore]. I think that was hugely important, historically. But, at least from what I’m seeing in the contemporary art scene, there is a negation of meaning, a total neutrality. A reversion back to pure formalism. In a way, that’s a reaction to the frustration with trying to deliver meaning within an image.

SG: When I opened this conversation, I talked about the resurgence of interest that’s visible in collage media. I’d be curious to know about your thoughts on its position in relation to more traditional forms of visual media, such as painting and sculpture, especially with regards to the market. What’s the work to be done, and can collage compete?

JK: That’s a great question. I think that collage is situated in a very difficult position, competing against more traditional media. Because of the nature of found imagery, there’s often less originality attributed to collage – unlike how we might look at a painting or a drawing as an original work of art as irreproducible.

SG: Even in such a reflexive market, where Sherri Levine can be considered a significant marker in our canon, are we really prizing originality to that extent anymore?

JK: For the most part, the kinds of work that I’ve seen that work in response to that idea of ‘lost originality’ seem to be producing enormously banal material.

But, to your other question, I’ve always really struggled with where to situate myself, especially being a printer and working with collage. Whether I’m supposed to be in a more populist market, or a more fine-art, high-end, restricted market. Regarding the frustrated position of making collage and trying to negotiate its position in the market, I’m producing images which I feel do have meaningful political narrative to them. But, not necessarily feeling welcome within the Toronto art scene – not seeing work of a similar nature. [Collage] work can be very boring, or neutral.

SG: Still, it should be acknowledged that artists who use collage, like Geoffrey Farmer and Luis Jacob – or more emerging collage artists like Jacob Whibley and Maggie Groat – are finding good success in both the exhibition circuits and, to some degree, on the market. Is the footing changing?

JK: There are a handful of collage artists who are succeeding, and through-and-through, their work is beautiful. But, it feels like each is a single artist within a much larger roster. Like the ‘token’ collage artist at a gallery that exhibits no others.

SG: What do you hope for the medium?

JK: That’s a difficult question. I feel like the availability of material and the relative ease with which anyone can make collage makes it, potentially, an Everyman’s medium. I think it can be difficult to distinguish between good and bad collage, which makes for a nasty value judgment. But, what do I hope for it? I hope for it to have a wider acceptance. Greater appreciation. That we as collage artists attempt to make less derivative work.

SG: How are you navigating the analogue and digital realms? Do you feel any sense of traditionalist loyalty to analogue, or is there are a lot of malleability between the two, at this point?

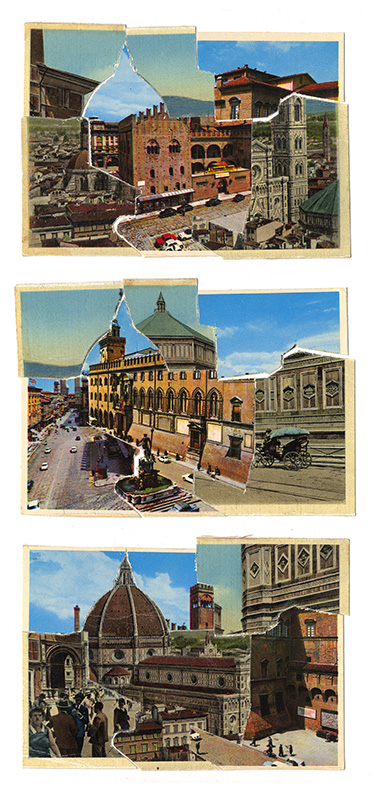

JK: Everything that I make is created in analogue form, with no digital intervention, aside from scanning very, very minor touch-ups – the removal of dust, specks of dirt that occur in the scanning process. The computer comes in really for the purpose of enlarging something. That said, I don’t want to pass judgment on digital collage. There’s an enormous amount of stunning digital collage. But, it’s never been an approach that I’ve been particularly satisfied with.

SG: It doesn’t irritate you, other artists using digital techniques? Like a kid with an iPod calling himself a DJ?

JK: To claim my position as a collage artist eight years ago, I relied on a pretty rigorous skill in hunting for original source material, for developing scissor technique, for learning to draw with scissors. And, when I look at a lot of the work on the endless scroll of blogs these days, it’s pretty easy to pick out images that have been repeatedly selected off of historical photographic websites. [Like], there’s another from Life Magazine, snagged from their website, composed on Photoshop.

What’s tricky about that now, though, as I position myself as a collage artist today, is to suggest that there’s some inherent essence to the analogue. That using scissors and glue is a more honest method or approach than using Photoshop or images that I’m able to Google. In a way, it’s potentially more effective as a narrative-driven medium now that you can search to the minute detail, the exact nature of the image you want.

I was recently hired by Penguin Books to remake one of my most successful collages into a new collage for one of their book covers, and the challenge was difficult. I spent the day in the reference library making an enormous stack of photocopies that I took back to the studio and got to work on, none of which produced any fruit. In the hours nearing the deadline I started Googling and got the images I needed. Printed those out, cut them apart – worked in my analogue style and came up with something that, in the end, I think is quite successful.

But, to be angry with some kid and his computer for treading on my hard-earned turf? It just seems a bit old-school and curmudgeonly now. I could say that I earned my stripes, and that this kid is riding on my back but, in the end, it comes down to what’s made.

SG: Are you resistant to the “collage artist” identifier, considering all the divergent work you do in other media and platforms?

JK: I think that “collage” is a difficult term in that, in the contemporary art world, it refers to cut-and-glue images. And now, in the digital world, the terms ‘cut-and-paste’ identify it. But collage, juxtaposition and appropriation extend through so many more media. So, when we talk about these things, do we just talk about works on paper? Is that really all we discuss?

SG: How should it be defined at this point?

JK: I would define collage as the use of juxtaposition to define something by the limit that it isn’t something else. So, by taking two things, and butting their borders up against one another, we really see what constitutes an entity, what closes the edge of something. In this world of infinitely proliferating, malleable, fluid content that’s overlapping and intermixing constantly, the collage medium helps us to see thresholds and behold the schisms.

What’s difficult for me, as an artist, though, has been to negotiate the meaning, worth and value of making works on paper. I’m looking around me and what I see in the art scene has not been hugely enchanting or inspiring. I’m not necessarily finding a particularly welcoming realm in the artworld for my collage work, but finding open arms in other territories.

SG: Walter Benjamin said about writers that they are “dissatisfied with the books which they could buy but do not like.” That this is their motivation to produce new texts.

JK: Right. You asked me the other day what gets me up in the morning. Well, I get up in hopes that each day I will be able to tell the story I haven’t yet heard.

Sky Goodden is the former Executive Editor of the popular contemporary art site, BLOUIN ARTINFO Canada. She regularly writes for Modern Painters, Art + Auction, Canadian Art, Border Crossings and cmagazine, among others. She was the 2010 Editorial Resident at Canadian Art, and holds an MFA in Criticism and Curatorial Practice from OCAD University. Goodden is launching a new online art publication, Momus, which will promote accessible art criticism and journalism, in Fall 2014.

art Art Gallery of York University Carousel Chronicle Books collage Fast Company Jp King Klondike Institute of Arts and Culture OCAD Penguin UK Sky Goodden Toronto Uppercase Whippersnapper Gallery XPACE