Elizabeth Zvonar's photographs bring collage into the digital age

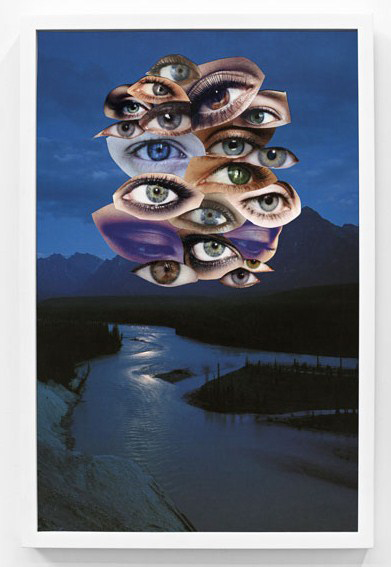

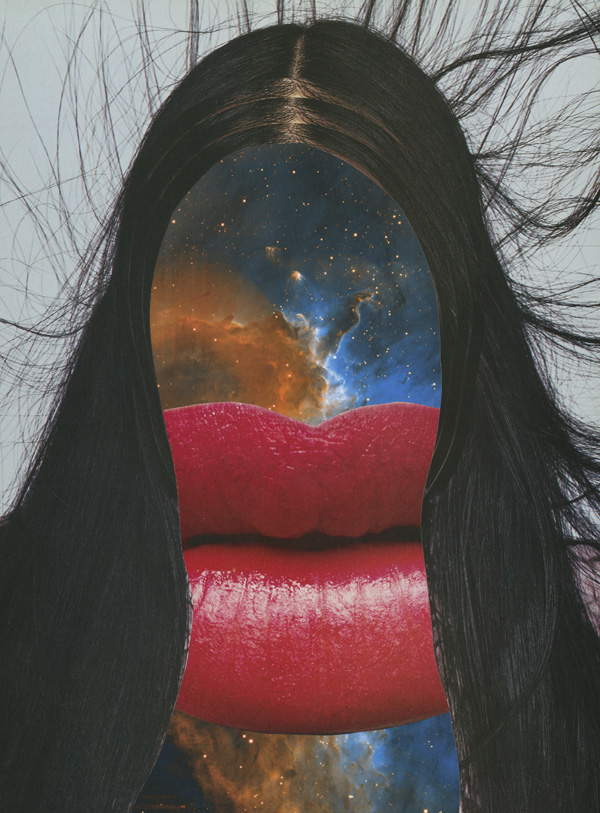

Vancouver-based Elizabeth Zvonar often produces her collage-based photographs from fashion and science magazines, as well as vintage lifestyle monthlies. By creating her surreal collages, photographing them and then blowing them up, Zvonar transforms the source material into something uncanny. Her strange and seductive images humorously touch on subjects ranging from the nature of daydreaming, feminist history, sex, the future and metaphysics. Her work has been exhibited across Canada, most recently at Gallery 295 in Vancouver this past spring. Here, artist Jason Gowans talks with Zvonar about her recent exhibition at the gallery, the influence of Eugène Atget, and what it’s like to make collage in the digital age.

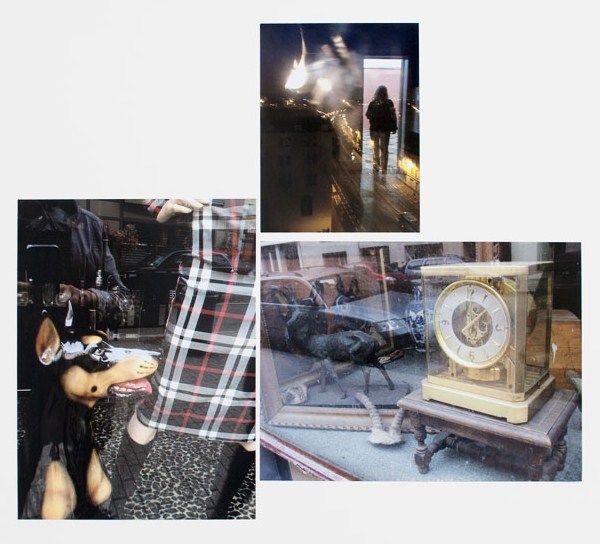

Jason Gowans (JG): Let’s start by talking about your recent exhibition. Most of I REALLY DO BELIEVE THE BEST THING A PERSON CAN DO WITH THEMSELVES IS TO EXPAND THEIR MIND consists of “mirror collages” that resemble some of Eugène Atget’s most famous photos, except done with a camera phone. This is a new direction for you – to show straight photographs – but, it’s definitely in line with a historical tradition of surrealist work that is linked throughout your practice.

Elizabeth Zvonar (EZ): There is a sensibility in Atget’s work that resonates with me and I appreciate the comparison. I wonder what it was like for him to wander the streets and record what he saw. It would have been so much more laborious and structured by the time of day in order to achieve the long exposures in potentially busy sections of Paris. It is the first time I’ve shown these works, but I’ve been making pictures for many years as a manner of note taking, or recording visuals to remember something.

It is so convenient, discreet and interesting for me to use my phone camera or small digital camera, rather than an SLR, which I have used in the past. The biggest hindrance to not using film might be the potential scale limitation for me, but my initial intention to take pictures is driven by how it absorbs me in the moment. The other objective for me would be recording a material I see that I want to use or something confusing that I come upon during my day that I want to remember. Sometimes, I come upon something that is unfamiliar enough that if I don’t take a picture, I’ll never be able to remember it exactly as I saw it.

JG: The amount of images that we have access to has changed in the past five years. Consequently, using images that are found in print material seems more like a deliberate choice. It’s almost the collage equivalent of using a film camera as opposed to its digital equivalent. Everything is slower and more expensive. Do you feel that there are still specific things that interest you in print material that guide your work through a specific historical trajectory?

EZ: When I make collage and use images from printed matter – books and magazines – I am making deliberate choices. Collage is a slow process by its very nature in comparison to how I take pictures. Making collage depends on time and space in the studio to be able to have images set up to compose and re-compose over months in order to get the composition that best works. The basic set up for collage versus film developing is cheaper but, because I scan, enlarge and print my collages out digitally, this expense combined with mounting and framing reflects that of printing film.

The specific content that I locate in printed matter is similar to how I might get absorbed when I take pictures in the world. The specificity of the materials that I use will guide the activity of making and it is possible to tease out an historical trajectory. However, I find the work I make that is most successful is duplicitous to its origins. It can relate in that there are familial genes, but it is its own thing.

JG: The creation of a collage is not particularly analogous to taking a photograph. However, they have both faced similar problems in the digital era. Having access to an archive of images to work with takes little more than an inkjet print and a computer. Doing a quick Google image search of “Mondrian” yields thousands of results. Some may be actual images of Mondrian paintings, others may be copies, and still more are simply using his design for coffee mugs. Borrowing images from the Internet seems to have different intention because it’s not archived in the same way print is.

Print, on the other hand, is very different. If I was to look in a National Geographic from 1990, I would have a clear understanding of the images I was looking at and where they came from simply because the photographer would have demanded it. It also presents uniform standards because lighting, films and cameras changed homogeneously from era to era. My feeling is that taking images from the Internet instead of taking them from print looks similar but presents two very different problems. How do you see this?

EZ: You’re right, different problems for certain. I don’t cull images from the Internet, nor do I create collages digitally. When I make collage, the beginning is an analogue process with scissors and glue. The last stage will be to scan the final image in order to end up with a high-resolution image that I can print digitally. I retain the cut marks in the final print as I prefer the image to retain evidence of the analogue process.

One of the main problems I see culling images from the Internet would be the sheer mass of amateur and professional images mixed with the variations of resolution. The value of using images from magazines and books would be the quality of the image to begin with, and being able to control the amount of images through the accumulation of the source material.

JG: We’ve been talking about the article by Trevor Paglen titled “Is Photography Over?”, in which he writes:

“Why look at any particular image, when they are literally everywhere? Perhaps photography has become so all-pervasive that it no longer makes sense to think about it as a discreet practice or field of inquiry.”

I have this memory as a child where someone is explaining the radio to me. They tell me that even though we can’t hear it, there is music all around us floating through the air and a radio is just a device that helps us find all that music so we can hear it.

I have this feeling about photography that it’s gone from being a physical object to omnipresent and around us at all times. It’s so thick that it feels like you could suffocate on the amount of images being produced.

Collage seems like one reasonable answer to this problem. Photographs have lost some of their indexicality but, in turn, it’s freed from itself and not bound to its own rhetoric.

EZ: You’re suggesting that pictures are ubiquitous in our day-to-day life to the point of stifling or to the point of saturation, and I totally agree. I think the visual culture we have made and are complicit with can be completely numbing. Increasingly, we are exposed to hyper-concentrated visual stimulation and it does something to our physical body through the necessary dumbing down of how we take it in intellectually. It’s a coping mechanism for us and the repercussions are terrifying.

This brings me to the last section of your question about the use-value of collage as a response to making images today. The sheer volume of material from which to make new images opens up the options, and I suppose applying a loose touch to making the work might loosen the tie to its own rhetoric, allowing for an open read.

JG: I’ve been reading some Chris Kraus lately. She cynically wrote, “It’s so – theatrical, is about the worst thing you can say about anybody’s work in the contemporary art world. Theatricality implies an embarrassing excess of presence, i.e., of sentiment. Because it’s more advisable to be everywhere than somewhere, we like it better when the work is cool”.

I’ve been admiring your ability to produce conceptually interesting artwork that also has emotive and spiritual connections. Looking at your work recently, I realized you produce work that I would not be brave enough to make. These subjects often equate to sentimentality and so often artists tend to stay as far away from them as possible. I found myself looking at works like Metaphysical or The Jesus Arms, and having a real emotional connection to the work. You seem to have a fine understanding of the space between humour and sincerity.

EZ: Humor and sincerity are two things I intentionally hone in my life and it makes sense this would come out in my art. Is sincerity still such an issue today? Are people still making work today intentionally devoid of emotion based on a mid-20th Century cultural protest? It seems so conventional for a contemporary practitioner to rely so heavily on history to provide an airtight, strict recipe rather than working with what came before in order to lay the groundwork for what could lie ahead, culturally. To make work institutionally seems like an antiquated way of making, similar to choking all of the life out of art. It’s impossible to my mind to want to be so regimented and predetermined when making work. I’m much looser in my process, and a lot of what came before passes through what I am doing in order to be able to make work that can be its own thing.

JG: Intention aside, having a belief seems increasingly difficult. You’ve worked with enough students throughout the years to see naïve enthusiasm crushed into cynical disinterest. Is the institution (or anyone) at fault here?

EZ: Well, I don’t teach, actually, so I’ve not worked in a conventional way with people in a student/teacher manner. I personally don’t believe its naïve or difficult to have belief in something.

The ‘institution’ across the board in any discipline can be problematic if one were to be ill-researched and believe that it will care about your future or support you. I don’t think that it is at fault so much as that it functions as a business model and has been increasingly transparent as it morphs and develops.

JG: Lastly, are there any recommendations you’d like to make? – Any artists or shows, books, food?

EZ: The Austrian artist Ursula Mayer’s show at the Audain Gallery at Simon Fraser University was super-fantastic. Just reading Silvia Federici again, and fully stocked with Trader Joe’s Thai Lime and Chili Almonds in time for the beach.

Jason Gowans is an artist based in Vancouver and Los Angeles. Read more about Gowans’ work in the Spring 2013 issue of Magenta Magazine.