Ulrike Arnold’s nomadic practice bridges the local and the global.

For over thirty years, the nomadic German-born artist Ulrike Arnold has maintained a dynamic traveling studio practice that evokes the image of an individual who refuses to stay still. Arnold’s practice interrupts the favored narrative of migration as an enforced, necessary movement that occurs across pre-established social, cultural and political lines. Rather, it traces the idea of a conscious, intentional “becoming lost” that operates at the very intersection between site-specificity and non-habitation.[1] For Arnold, the studio without walls is a tool for losing oneself in the landscape — a self-reflexive migration of ceaseless retreat and solitary reflection.

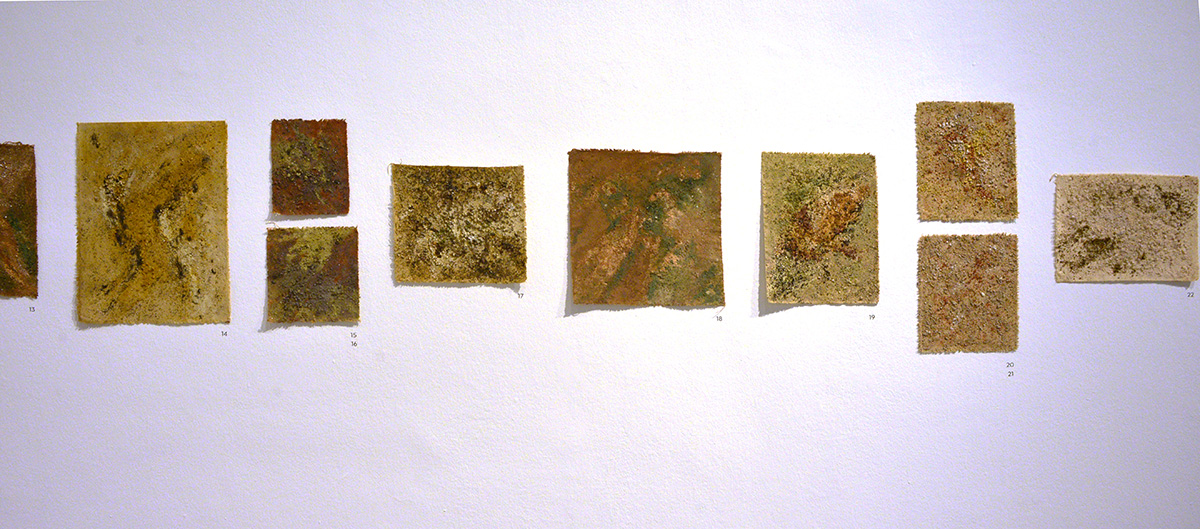

All of Arnold’s self-identified “earth paintings” are sourced from and constructed directly within the remote environments she visits around the world. While working onsite, she utilizes unstretched raw canvas to create abstract compositions with found pigments and other available natural materials. Upon completion, these canvases are extracted from the landscape and presented in the gallery space, where they are either draped against the wall or spread out on the floor. Arnold’s artistic practice blends together three mediums – painting, sculpture and an unconventional mode of performance art.

At the site of this intersection, Arnold’s studio without walls is never consistent across geographic spaces, always already shifting according to the native materials that become available. It is, then, better described as auto-ethnographic “field work” that exceeds the boundaries of the conventional academic art studio as an enclosed, delimited and supposedly neutral space for measured experimentation. In this respect, having worked on the earth paintings series in all six continents, Arnold’s practice embodies a kind of restless, nomadic approach to land art. As opposed to earlier discourses in land art that focused on fixed, monumental structures and spaces carved into existing landscapes, the earth paintings self-consciously embody the distances between ideas such as the local and the global, the territorial and the expansive, and the placed and the displaced. On the one hand, her practice is decisively site-specific; and on the other, it cannot simply be defined or grounded to one region, as she is constantly moving in, around and between rural landscapes.

What is the locational identity of this body of work? Arnold has created earth paintings in spaces that include Yemen (1986), Togo (1992), Tenerife (1996), Utah (2008), and Easter Island (2012). Most recently, through numerous residencies conducted between 2012 and 2014, Arnold created an extensive series of canvases in the sweltering Atacama Desert located west of the Andes on the Pacific coast between Peru and Chile. In addition to her ongoing earth paintings series, Arnold continues to work on an offshoot “meteorite paintings” series, in which she creates similar abstraction works but with ground up authenticated meteorite rock, as well as a “rock art” series in which she works directly onto iconic rock formations around the world, which include the Zen monastery in Crestone, Colorado (1991) and the Badami cave temples in Karnataka, India (2001).

In each of the earth painting series, Arnold uses abstraction as a technique to respond to the immediate landscape. These series are distinguished by certain compositional elements that can be linked to each site. Where some emphasize a heavy use of perspective, others may employ a vibrant colour field technique or simply remain soft, restrained and neutral. For example during a 1999 residency in Itabirito, Brazil, Arnold created a collection of elegant, fluid abstractions in orange and mauve, while the works created in Arizona between 2006-2008 present highly gestural, almost aggressive works made primarily in shades of grey. Here, one of the great mysteries of the earth paintings emerges out of the tension between the abstract formal (non) disclosure of the image and the pictorial differentiation occurring across and between sites. For example, how could we, without having any access to certain research materials, distinguish between works created in Yemen, Senegal or Arizona?

In November 2014, Arnold presented the work produced during the Atacama residencies at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo in Santiago Chile. The exhibition, titled Atacama: Cielo y Tierra, brought together a wide selection of earth paintings, as well as several documentary materials to provide necessary context to the artist’s migratory practice. Presenting 36 canvases in total, this series reflects of Arnold’s remarkable productivity, and illustrates the figure of an artist committed to pushing the material and conceptual boundaries of painting through an eccentric, laborious creative process. The title translates to both “Sky and Earth” or “Heaven and Earth,” which, in either case, is evocative of the artists’ deep interest in astronomy and, accordingly, her extensive use of meteorite rock in constructing these works. Here, one might reflect on the fact that a meteorite is visible only as a trail of light in the night sky. In this metaphoric sense, the earth paintings are better understood as the contingent traces of Arnold’s activity in Atacama.

Given the artist’s detailed site-identification labeling scheme, one quickly notes the similarities between works created in the same regions of the desert. For example, both Monturaquikrater (24) and Monturaquikrater (25) (both 2013) are made with intricately blended deep browns, reds and fluid streams of ivory, while Parnal (30) and Parnal (34) (both 2013) consist of lighter browns with loosely dispersed dark elements. Where these four works are held together with extremely subtle colour and textural gradations, others like Quebrada de Tulan (1) (2012) and Cordillera de la Sal (2013) are far more gestural and bold in the use of form. Even considering her seemingly obvious limitations to a neutral colour palette, Arnold achieves a considerable amount of compositional variety throughout the series, experimenting with various stains, gradations and unusual layerings of shards, granules and sediments.

It is also important to note the documentary materials that accompany many of Arnold’s museum exhibitions. At the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, for example, visitors encounter a series of photographs taken of the sites in which Arnold had worked, ranging across the 1,000-kilometre Atacama landscape. A documentary video work placed beside the photographs provides insight on the intricacies of Arnold’s process, whether searching, walking, sleeping, painting, or researching with an astronomer about the Monturaqui crater in the Atacama salt lakes. The video represents Arnold’s work as rough, imprecise and intuitive. She uses the brush with a heavy hand, drags the canvas through the dirt, steps on it, and washes away at unfavorable markings with dirty water.

Arnold works against conventional modernist sensibilities tracing the absolute importance of “formal singularity” and “material consistency” by treading at a liminal space between the micro and macro view of the landscape. Paradoxically, the earth paintings begin so intimately at the level of the ground, and yet in their final presentation, they appear to take on a topographic quality. We imagine the artist looking down at herself from above, mapping her movements in a formal language only she can truly understand. Arnold’s commitment to abstraction stages the impossibility of an essential, whole representation of the landscape. In short, even the most refined photographic technologies fail to evoke the distinctive migratory bond she forms with the landscape. In this respect, Arnold’s abstractions do not simply identify disinterested formal explorations of colour, texture and composition, but rather express the desire to reach behind the pictorial and think beyond the visual. Upholding this migratory movement for its own sake, her abstractions begin to reveal themselves, however paradoxically, as representations of the non-representable, ever-shifting experience of the moving body in the empty landscape. This consideration does not emerge from an attempt to view Arnold as capturing a kind of overarching, mythological essence of the desert. Rather, we must focus on the bodily aspect of retreat itself, and therefore consider this as a nomadic practice, always already in transition from one site to the next.

Taking on the role of an unstable subject at once present and absent in the landscape, one might state that Arnold works en plein air, but with transnational sensibilities. Although Arnold does not travel to spaces that are divided by political unrest or civil conflict, to assume that her work is somehow politically neutral is a critical misreading. We see, instead, the emergence of a migratory, nomadic politics emergent through the figure of the restless body. The nomadism of Ulrike Arnold is expressed by way of a decisive retreat from urban space, motivated by an interest in the formal language of the sand dune in the rural desert over the piercing skyscraper in the crowded city street. This sense of purposeful, ceaseless retreat reveals a complex autobiographical element that cuts across Arnold’s oeuvre – in particular, that her sense of belonging must be continually called into question for the studio without walls to retain its basic purpose as a tool for solitary reflection. In this state of transition, Arnold becomes an unstable artist-subject with no necessary place to return to do her work. Realized together, then, the complete six-continent earth painting series offers a fragmented, incomplete atlas of a restless, always already deferred self.

This mode of ceaseless retreat that animates Arnold’s studio without walls can be read through Daniel Buren’s often-cited writings on “the function of studio.” Principally, as Arnold makes portable objects in a portable studio, her process interrupts Buren’s key argument that the studio is “a stationary place where portable objects are produced.”[2] Yet, taken further, Buren’s text allows us to consider what is lost at the moment when these works are extracted from the landscape and (dis) placed into the gallery. [3] Arnold self-reflexively straddles the distance between the gallery and the studio by emphasizing the precise material specificity of these objects. Whereas Buren most iconic works call attention to the immediate “place” of the installation, Arnold builds her institutional critique from the inverse by suggesting that the landscape can never fully be reduced to fit inside the gallery – in short, that her experience of the landscape can never be reduced to a mere representation. Instead, her works can only ever represent the fragmentations and extractions of a prior movement onto a lost site.

If we choose to view Arnold’s work as a decisive rejection of the global institution called “contemporary art,” her retreat into the rural landscape is best figured as, what Imre Szeman and Sarah Blacker refer to as the “restitution of the body and a syncopation of time that comes all to infrequently in the hurry-up time of late capital.”[4] In this respect, Arnold’s studio without walls inverts the popularized 21st Century figure of the globetrotting and Instagramming contemporary art star. This point is not meant to romanticize Arnold’s practice as inherently innocent or holistic, but to emphasize that her relatively low profile international art market presence has at the same time built her reputation as an artist practitioner deeply and patiently committed to the integrity her craft for its own sake.

Arnold’s migratory practice links together three key phenomenological positions: the direct relationship between hand, material and canvas, the body travelling through the landscape, and finally, the topography of the depths and valleys which define her path. Here, we quickly realize that with any attempt to categorize Arnold’s migratory practice, the inverse of any seemingly defining characteristic must also be true: to be site-specific is to be placeless, to arrive on-site is to depart, and to reject metropolitan life is also to engage spirited politics of retreat each and every time the studio without walls is performed.

Work by Ulrike Arnold is on view in the group show Natural Affairs at QuadrArt in Dornbirn, Austria to November 1, 2015. Other artists featured in the exhibition include Josef Beuys, Ana Mendieta, Franz John and Daniel Spoerri.

[1] Rebecca Solnit, A Field Guide to Getting Lost, (London: Penguin Books, 2006), 6.

[2] Daniel Buren, “The Function of the Studio,” October 10 (Fall 1979): 52.

[3] Ibid., 56.

[4] Imre Szeman and Sarah Blacker, “Between the Exception and the Rule,” Public 25 (Fall 2014): 9.

Adam Barbu is a writer and curator living between Toronto and Ottawa, Canada. His current work focuses on queer theory and the politics of spectatorship. In 2015, he was the recipient of the Middlebook Prize for Young Canadian Curators.