Sarah Anne Johnson joins internal and external worlds

In conversations, interviews and artist talks alike, Sarah Anne Johnson has bemoaned the difficulty of translating experience into a photographic image. The instant anything is framed by a viewfinder, the subject becomes object and an immediate distancing occurs. Throughout her career Johnson has attempted to collapse this distance in a variety of ways: by photographing memories she’s constructed through dioramas; showing sculptures that act as extensions of the image; and painting on and cutting into photographs. Most recently, she’s done away with photos altogether in favour of video and performance. This change, however, hasn’t necessarily brought her any closer to resolving the dilemma at the crux of her practice.

Johnson’s struggle has always been between internal and external space, or the gap between the world as it is and the world as we see it. Ironically, her move to performance, rather than bringing these polarities closer, might actually be pushing them further apart. One set of conventions is replaced with another, begging the question of whether this is a separation that can be bridged, one that we ourselves produce, or simply a brute fact of life. Inarticulate interiority, when translated into art, must always wrestle with the constraints of form, though it is through these very limitations that the underlying chaos takes shape into something productive.

The archetypal meeting point of the internal and external might be the house, especially the childhood home where the growing psyche takes shape. For Johnson, parts of the home come to represent aspects of the mind along the lines of Gaston Bachelard’s Freudian divisions that relegated the Id to the cellar, the Ego to the main floor, and the Superego to the attic. Though his phenomenology is markedly more sentimental than Johnson’s, Bachelard does point out that domestic space inhabits the psyche just as the home is inhabited by the body. Etched into us are the feelings, habits and impressions of our intimate milieu, which we subsequently project onto new spaces we encounter; as Bachelard writes in the Poetics of Space (1958), “we bring our lares with us.”

This domestic psychology has structured the spatial relations in Johnson’s work as well as the organization of her exhibitions, especially her CAM Raleigh mid-career survey in North Carolina last spring. The gallery’s basement was home to clandestine interiority; the works exclusively referred to happenings behind closed doors which, in this case, included sex, mental illness and theft. The stairwell marked a thematic transition with the installation of an immersive lenticular print picturing a coniferous forest at night, while the two-storey main floor housed her outdoor environmental projects. Sculpey figurines were arranged on plinths while photographs depicting fragile ecosystems climbed the height of the walls. Though the gallery lacked a third floor, the soaring size of the main space was emphasized by salon-style hanging and a sculpture of a massive, multi-coloured, plastic cloud spreading across the ceiling. Because of their sober environmental references, the images seemed to play the role of our Superego, the conscience, while the pleasure-seeking Ego, situated on ground level plinths, took the form of doll-sized figurines making silly faces for the camera.

Johnson’s strategy has been consistent: she visits and photographs a unique, highly psychologized site, then later projects her own state of mind onto it by reacting to the documents she’s produced. The places are chosen for the way they problematize boundaries, both internal and external. Her early Galapagos Project (2007) is one such example. The islands are a designated UNESCO heritage site because of their unique ecosystem and role in Darwin’s development of the theory of evolution, making them both a protecting and protected space. Johnson traveled there as one of a number of eco-volunteers to document their shared experience. It is the first exhibition in which she included a model of her accommodations—a multi-level communal shelter where staff did chores and rested. Arctic Wonderland (2011) portrays another fragile ecosystem whose boundaries, though porous, are highly defined even if politically debated. Located at what is popularly imagined as the top of the world, the Arctic has become our global Superego, the environmental conscience that acts as a litmus test for the health of the planet. Her last series of photographs, Wonderlust (2013), straddles interior and exterior by revealing the solitary or shared sexual intimacy of strangers in their homes. The images are augmented with Johnson’s fantastical, and often aggressive, interventions that include scratches, cuts and burns. Rather than expressing the expected passion of the performers, the added marks are evidence of the artist’s continued frustration with the ultimate muteness of the image that is supposed to be, as the cliché goes, worth a thousand words.

For Bachelard, the house is a protective space for pleasant daydreaming but, for Johnson, it can be a cover, a trap or a nightmare. Homes are microcosms that create and normalize certain ways of being — it is no coincidence the word “habit” is found in “habitation.” House on Fire (2009), consisting of bronze sculpture, a dollhouse and augmented photographs, is the only project directly dealing with the artist’s childhood home and, as such, slightly diverges from the schematic defined above. It is a topic to which the artist has once again returned even if the site is one she no longer goes back to; it is the “lare” she carries with her.

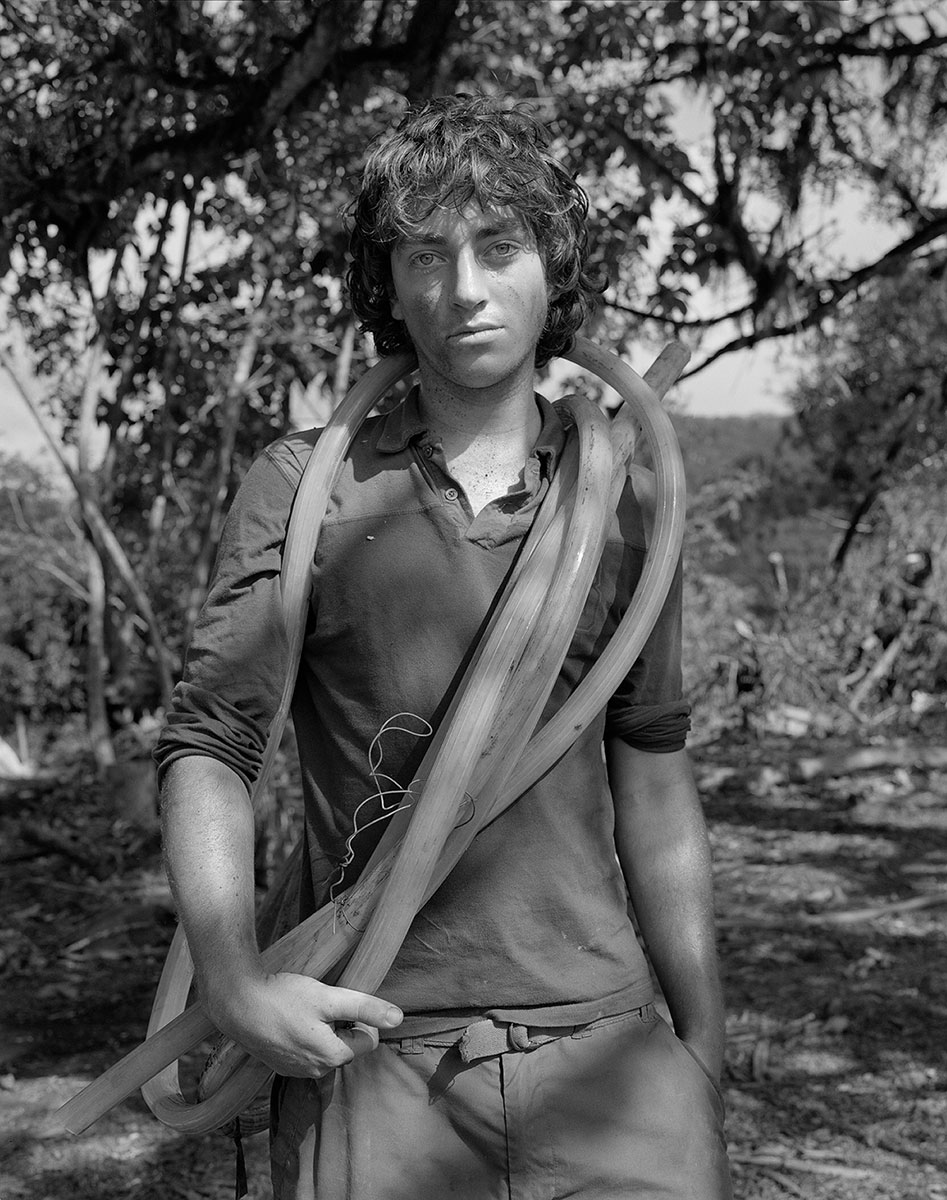

House on Fire grew from Johnson’s inherited archive — tapes, letters, newspaper clippings — detailing her grandmother’s stay at Dr. Ewen Cameron’s now infamous psychiatric ward in Montreal. Dr. Cameron’s hospital was the site of CIA-sponsored experiments conducted as part of the illegal Project MKUltra, the goal of which was to extract information, then empty and reprogram the human mind. In itself an egregious mixing of interior and exterior, the program left many patients permanently damaged, including Johnson’s grandmother. House on Fire was a literal means of examining her grandmother’s experience and connecting it to the family dynamic that coloured the interior of her childhood home. In the artist’s representation, this is a house with its id run rampant. What, in Bachelard’s poetics, was consigned to the basement, has made its way upstairs, through the main floor right up to the airy attic — the natural dwelling place of the Superego. Johnson’s house, rather than shielding its inhabitants from the dangers of the outside world, hides chaos behind a veneer of respectability. In a dollhouse version of her childhood home, a tree grows through its centre overtaking parts of an already disrupted interior where furniture sits on the walls and ceilings, psychedelic patterns crawl across surfaces and snow piles inside rooms. Her augmented family photographs, scanned, enlarged and then painted on, follow a similar trajectory. Typically familial scenes are sites of fairytale augmentations whose aesthetic seems simultaneously childish and mature. In one photograph vines entangle family members together, while in another, a giant squirrel head stands in for her grandmother’s face.

In 2008, when Johnson and I first met in Banff, the artist was beginning the lengthy exploration of these archives. Already, she was projecting a dynamic body of work that would take shape and change over the years. The volume of information alone, she would note, was so large that she couldn’t possibly go through it all. Seven years later, in a new work shown at the 2015 Sobey Award Shortlist Exhibition, Johnson still hasn’t delved through the entirety of her inherited documents though she has found a different way to engage the history that has left an indelible mark on her psyche. Ironically, it is a history that, despite its careful, clinical documentation, remains frustratingly inaccessible.

Rather than illustrating aspects of the archive, Johnson has built an enclosed space that embodies the claustrophobic rage underlying her family home and, presumably, her grandmother’s mind. Titled Hospital Hallway, the space is a hexagonal room with a pillar in the middle meant to look like an institutional corridor perpetually leading into itself. Inside Johnson performs wearing a high contrast Xeroxed black-and-white mask of her grandmother’s face, a wig, an off-white chiffon blouse and grey pants. The room is starkly lit by long fluorescent lights and the grey colour of the floor extends upward to form a trim at the base of the walls. There is no proper door; one wall is constructed on hinges that seamlessly blends with the others when drilled shut with the artist inside. Within this claustrophobic space, Johnson performs a variety of histrionic acts causing her both mental and physical strain. The 40-year-old artist has retrained herself in dance techniques learned in childhood so that she can throw herself from wall to wall, slither across the floor or spin in circles by pushing herself off each surface. At the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Johnson presents each action looped on small LCD screens affixed to the walls. The audience is invited to enter the space but unlike the performer, the doors are not sealed shut and they can leave whenever they want.

The most disturbing presentation of Hospital Hallway happens this winter at the Southern Alberta Art Gallery. Johnson will perform in the hallway with the audience standing on a platform built around the space. Looking down into the room, as I have in the artist’s studio, one is immediately put in the position of the psychologist observing her patient, or a scientist watching lab rats. The audience is not witnessing the trauma of her grandmother, as much as the artist’s attempt to bridge her own personal and aesthetic struggles.

Covered in bruises and scratches from the performance, Johnson has still not succeeded in breaking free of the frame. In an effort to bridge the in with the out, she has provided herself with an experience that just might be the equivalent of banging one’s head against a wall. As she cuts away the barriers between herself and the experience of something she can never truly feel, she pries harder at an impossible task hoping that, in the end, something will give. There is a heightened theatricality in the live performance and the documentation alike. The room functions like a gallery within a gallery wherein Johnson has hung new pictures though now they are moving. The exterior is rough and unfinished as a tacit admission of artifice. The mask she wears is effective as an emotive, almost shamanistic, device though it makes no attempt to disguise what it is. The wig she wears is almost comically artificial. Johnson’s techniques, while constantly attempting to move beyond the frame, are, in fact, structured by it.

The sites that Johnson gravitates to are already framed. They are places suffuse with emotional surplus like myth, longing, secrecy or anxiety. Their boundaries demarcate a space of experience that asserts its singularity, even while the artist attempts to repeatedly transgress those borders. When she returns to her images and paints on top of them, she is not only reacting to the objectifying function of the camera, but to a range of cultural framing devices that have rendered each site a symbol of something more. Her sculptures and her photographic augmentations, rather than intensifying the expressive quality of a document, seem to be a means of incorporating experience into subjectivity; it’s a way of making it her own.

In previous projects, her frustration with presenting firsthand experience lay in her inability to communicate the complexity of a lived moment. Her grandmother’s story, on the other hand, is one that she’s never lived herself and so it becomes the ideal vehicle through which to engage her aesthetic and conceptual dilemmas. With the expanded version of House on Fire, she doesn’t replicate events as much as create new experiences to function as surrogates for ones she’s never had. Hospital Hallway is only the newest of what will be other re-envisionings of a history that can never be adequately told. No amount of documentation can relate the trauma of one woman and how it affected the generations of women after her. It seems to me that Johnson has stopped trying to do so. Instead, she has found a way to use the frame as a means of producing experience rather than isolating it via the logic of a viewfinder.

Sarah Anne Johnson’s Hospital Hallway is on view at the Southern Alberta Art Gallery until January 31, 2016, and then travels to Division Gallery in Toronto, opening on March 19. On April 1, Johnson’s latest work, The Kitchen, opens at Gallery 44 in Toronto. Both works are presented in conjunction with the Images Festival, which officially runs from April 14 to 23. Johnson’s exhibition Field Trip is also on view at Division Gallery’s Montreal space until January 30, 2016, and then opens at the McMichael Gallery in Kleinburg, Ontario, on March 5.

Dagmara Genda is an artist and writer. Her publications include Border Crossings, Canadian Art, Momus, and C Magazine. She has written numerous catalogue essays for public galleries and artist-run centres, and served as editorial chair at BlackFlash Magazine. Genda’s art has been shown at the Walter Phillips Gallery, Esker Foundation, Contemporary Art Forum Kitchener + Area Biennial (2014), as well as numerous public and private venues across Canada and the US.

Division Gallery Gallery 44 installation manipulation photography Sarah Anne Johnson Southern Alberta Art Gallery