David Altmejd and the power of materiality.

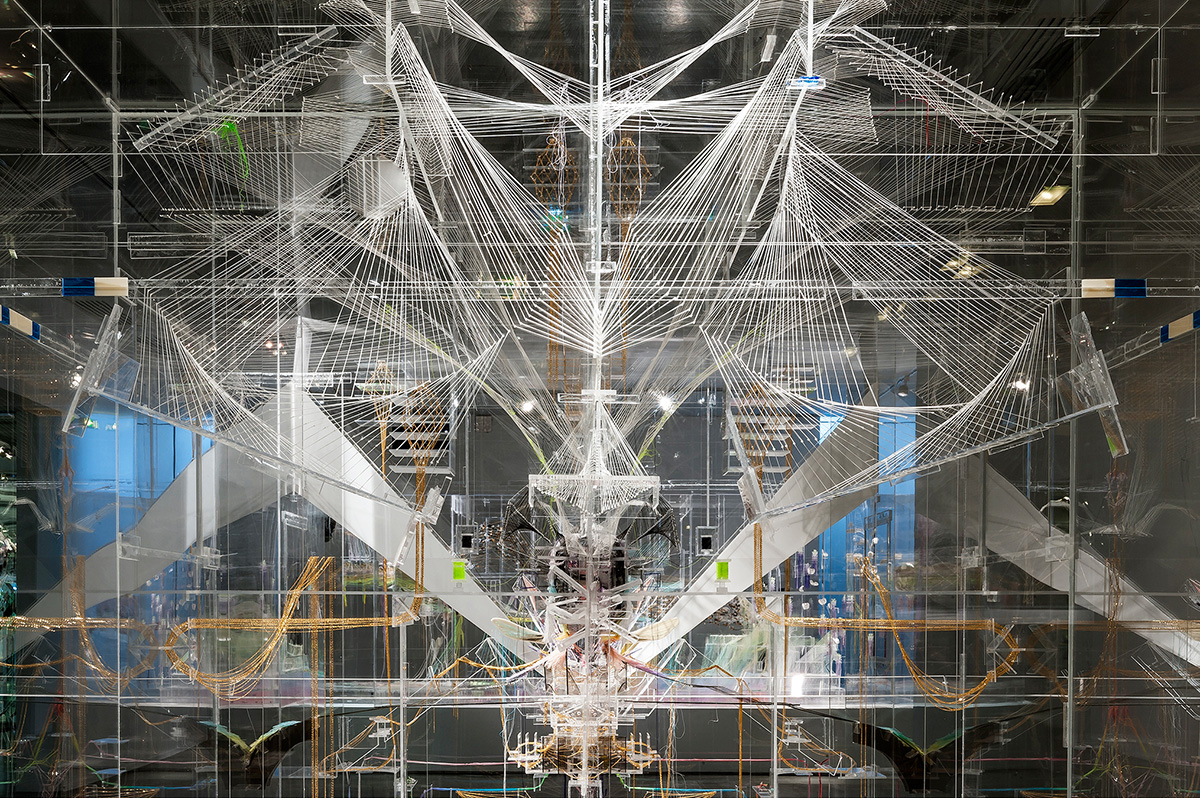

Energy, potential, infinity, evolution: the words David Altmejd uses to describe his work have multiple valences, from the analytic and scientific to the psychedelic or spiritual. The intricacy of the New York-based, Montréalais artist’s practice is evidenced in its expansive production, with layers upon layers of meticulously accumulated objects bewilderingly arrayed. Alternately precious and profane, humble and extravagant, Altmejd’s sculptures contain whole worlds, each with their own peculiar ecologies, philosophies and physical laws. Yet for all their complexity, his works speak directly and profoundly to the senses, rendering them exceptionally legible to audiences of all stripes.

Altmejd has exhibited widely in North America and Europe, and represented Canada at the Venice Biennale in 2007. His first retrospective, Flux, has appeared at the Musée d’art moderne in Paris to the Mudam in Luxembourg City. Montreal-based writer (and Magenta’s Reviews Editor) Benjamin Bruneau interviewed the artist earlier this spring in advance of the retrospective coming to the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal in June. Here, they talk about how spaces affect art, art affects bodies and the artist’s exploration of Instagram.

Benjamin Bruneau (BB): How do you feel about your how your work has inhabited the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris and then Mudam in Luxembourg City? They seem like different shows entirely.

David Altmejd (DA): It’s so interesting how the venue’s architecture determines how the work is presented. Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris has a very linear space, made of long hallways and narrowish rooms, one after the other. We had no choice but to install the work in a linear way, one sculpture after another, so the installation ended up being a story. It’s an odd space, which I liked. It’s very complicated. I was a little nervous, because France has such a strong intellectual art history. The North American perspective is so different, because it’s obsessed with the present—what’s happening right now. Most of the time, when my sculpture is exhibited here, I want to make sure that it exists intensely in the now. I was concerned that in Paris, in a history-obsessed culture, my work, which is not made from that space, wouldn’t live the same way. But, seeing my work in that context, and seeing that it functions well and speaks well in that context, was very meaningful for me.

At MUDAM, the work is installed either in enormous atrium spaces blasted with natural light, or in super-controlled galleries. The atrium light makes the work look like actors in an overwhelmingly bright landscape, in a good way. The controlled and contained gallery spaces let the viewer relate super-intimately with each sculpture. So, there’s the great outdoors in which you feel very small, and then there’s the intimate bedroom where you focus on every square inch of your lover.

The show in London was a show of just heads, and that required a lot of production, but it’s intimate work, on a small scale. For me, it’s like drawing — I don’t really think of the head in a conceptual way, but more like a frame where I can experiment with different textures and colours.

BB: And now you’ve begun doubling them, making a head and then turning them upside down and rebuilding them. A lot of your work seems to have a significant amount of symmetry.

DA: I have different ideas about it, but symmetry is a simple way of making chaos look ordered. Sampling a bit of chaos and repeating its mirrored image makes it look like an ordered system. But, symmetry also makes reference to the body, and it also makes reference to a kind of sacred, almost Catholic visual system. The cathedral, the crucifix, it’s all symmetrical. It’s a system of imagery that contains a lot of power, and I’m very attracted to that aspect of symmetry, as well.

BB: You’ve worked on very large projects like The Index and The Flux and Puddle, and very small ones. In what ways does scale change your work? How does it affect your concerns, your intent? Is scale important to you?

DA: I don’t really consider scale as being an important characteristic in an object. Objects of any size have the potential of containing infinity, and that’s what I am truly interested in. It’s really important that every time I make a piece, whatever the scale, it has to have a feeling of complexity. It has to contain infinity. So, a head would not just be a small section of a larger piece. In my mind, it functions the same way as a larger piece. The biggest difference between a small sculpture and a large one is that the small sculpture is made from the outside and the larger one is made from the inside. In that way “large” is just “small” turned inside out.

BB: You’ve said that some of the most important work you’ve made, like The Index, The Flux and Puddle or your first werewolf pieces were so big that they took over your studio — that you were working on them but also in them. In taking over the studio and becoming the studio, do the works themselves become centres of production?

DA: I think so. I’ve always thought of them as the producing energy. All the energy that comes from making a work from the inside is recorded, in a certain way, in the object. The object still contains that energy.

BB: I’ve certainly always felt as though they’re producing affect or emotion. It reminds me of Iain Banks’ novel The Wasp Factory, where this boy builds a barbaric machine to predict the future. He feeds wasps into the machine, and the path they take through its innards affects how the future unfolds. The more time I spend with your work, the more I start to feel like those wasps — depending on where I go, I come out feeling completely different ways.

DA: I really like that potential. I’m very interested in seeing the work as a machine that can produce things, but I’m not interested in what it makes. I like knowing that the work will be able to speak, and that it has its own intelligence, but I’m not interested in what it says, or what it generates. I really like the idea of the sculpture not simply being there to communicate something that already exists, but rather producing everything.

BB: How important is the viewer’s body to you when they’re interacting with your work? You’ve recounted that at the Canadian Pavilion at Venice people “let their guard down” and had trouble navigating the installation, and were unsure of the space their own bodies took. Was that your aim?

DA: I see the body as an object that contains infinity. When two bodies relate to one another, there’s this proximity between two infinities that I find so profound. I don’t expect viewers to have that kind of experience, but I would love them to at least feel like the sculpture exists in the world a little bit like they do, that it breathes the same air, and that it has a lot to offer.

BB: I was struck, watching a segment on Art21 where you cast one of your ears, that surely you had cast your ears before that moment. In casting a new ear, are you engaging a new facet of yourself? When you place your body into a work, is it important that it’s a piece of you now?

DA: First, during the process of building it, it makes me feel more intimately connected. Like I’m fingering it or something. Second, at a more conceptual level, it makes me feel like it’s coming from me, as if it were my child. It carries things that came from me, but is also it’s own person.

I don’t think meaning exists before touch and material. They are the origin of everything else. I want to draw attention to that. It’s not as if the hand and the material are tools, they’re the origin — everything comes from that. The work can then develop its own intelligence. There’s some of your own DNA in there.

BB: I’m really interested in how you use social media. You use Tumblr and Instagram a lot.

DA: I’ve started trying to explore these spaces because they’ve become so important in certain ways. I get many more visitors to my website or Instagram than any museum show. Being a sculptor, it’s not necessarily natural to develop a presence on those platforms, and my presence is not sophisticated, but it’s possible to be very creative there.

BB: And immediate!

DA: Yes, it’s so spontaneous. It’s so easy to post something, but it’s not at all easy to install a sculpture in a gallery. It takes months to make a sculpture, and months to organize the installation, so you have more than enough time to make sure that you’re okay with putting that part of yourself into the world where everyone can see it. Posting an Instagram photo is so easy— it’s hard not to look back at it and cringe at 80 percent of it.

BB: But, it’s so illuminating. It also seems incredibly consistent with what your body of work. You can see ideas being worked out in some of those photos that are mirrored in the heads or in other sculptures. And, it’s so weird and delightful. Art on social media, and Tumblr in particular, is really peculiar.

DA: A post on Tumblr can have a life of it’s own. On Instagram, photos only go out to a small circle of people, but on Tumblr it can go on potentially infinitely. The sensibility is completely different than any other media, too, because it’s uncensored. It can be very sexual or gory.

BB: There’s so little differentiation between subjects on Tumblr. You can have fashion, gore, art, sex, a cat photo, a selfie all on the same page. It accumulates, and the way you experience it is as an accumulation. You don’t look at just one image, or just one video.

DA: Because of that, I’d like to explore what kind of presence I can have on those platforms. Not as documentation, not just to transpose my work to that space, but to make things that are appropriate for the digital space. Video is something that I’m trying out.

BB: In some ways your work already seems digital, moving between elements within sculpture. The chains in particular are like hyperlinks. Between references, materials and proximity, there’s a very dense interrelationship.

DA: Within one piece, I like that there can be infinite details. It’s not about having a controlled experience, but rather about movement, seeing yourself move through the work.

BB: Mirror and Plexiglas, as you use them, seem to be virtual materials, both there and not there.

DA: That’s the reason that I started using them. I wanted to make things look like they were floating, to elaborate complex structures in space. But when you’re in front of it, close to it, it becomes extremely physical, with a presence with a life of its own. Mirrors, too, are a material that multiplies space, but don’t present as things in themselves. But even the first time I used mirrors, they cracked, and through the crack you can feel the materiality of it. You can feel the weight, the danger of cutting yourself. It gains a strong material presence.

BB: In the catalogue of the 2008 Quebec Triennial, you mentioned that a video game catalysed the series of giants that you produced around that time. Is there anything about the structure or function of games that you find particularly compelling?

DA: I love games that present themselves as landscapes that contain everything—hidden treasures, friendly characters on the other side of the mountain, monsters in the forest, etc—before you even start playing it. What inspires me is the game before I play it, when I can feel it’s potential. I fetishize potential.

BB: You seem to accumulate processes without discarding them. When you find something that works, you keep it—werewolves, ears, chains, mirrors, more recently fruit. The work gets more complicated as you go along.

DA: I think that’s how people are, how you evolve as a human being. I like the idea that a sculpture would function the same way, would be able to grow into the same complexity and richness as a human body.

Altmejd’s exhibition Flux opens along with an exhibition by Jon Rafman at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal on June 20 and runs until September 13, 2015.

Benjamin Bruneau is an artist and writer based in Montreal (Tiohtià:ke), on Mohawk and Abenaki land. He is the Reviews Editor of Magenta Magazine.