Three Toronto artists play with installation views.

Blow-Up, Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 cult film, was a short story by the Argentine author Julio Cortázar first. Before he was streamlined for the screen, Cortázar’s photographer-protagonist was radically unreliable, scrambling syntax from the start by narrating in first and third persons, present and past tenses. Centred around his experience, the written story presented the individual photographer (who was even both dead and alive) as a surreal ensemble.

The notion of photographer as multiplicity jars, and resonates. In industry jargon, most photos are “monofocal”: they reify a single perspective. But a vantage, like an atom, can be divided, and an individual can serve as proxy –for a collective, say, or future selves.

Photographers who document art are especially sensitized to these dynamics. If art is subjectivity par excellence, the influence exerted in its documentation is particularly fraught. In preserving shows, photographers become collaborators with significant power to shape the art they record. The photos Brancusi took of his own work feel so personal that critics compare them to letters and journal entries; in Chicago recently, Christopher Schreck curated a show of atypical installation views. And, increasingly, contemporary art itself is addressing the influence of exhibition documentation.

The three Toronto-based artists below directly engage the conventions of installation views. Their orientations vary, but common themes pervade: all negotiate the differences between their practices and others’; all approach galleries site-specifically; and all commit to images, and invest in their perpetuation.

Lili Huston-Herterich

The protagonist of the original Blow-Up is no glamorous professional. He photographs for leisure, and his oblique relation to the craft proves important. Though a trained photographer, artist Lili Huston-Herterich likewise acknowledges the force of amateurism. Her work mobilizes the whimsy of mark-making against the dourness of technical perfection. She has painted bold dashes on plant leaves and tested nail polish across the pane of a colour print. To emphasize the bias of frames, she’s made conspicuous modifications to many of hers.

For her solo show Pleasure of A Lazy Laity at Xpace this past fall, Huston-Herterich writ her interests architectural, decorating baseboards with irregular brushstrokes and cutting carpet into gestural swaths. Homemade garments hung on hand-painted hangers. The point was to customize ad absurdum: to evoke, with various finishes, a sense of the never-ending.

The installation privileged function: it offered its fixtures as furniture, not sculpture. Showcasing a photographer’s knack for getting out of the way, it self-effaced for others’ ends. The personal touches, though pervasive, were anonymous: the artist’s marks were not signatures. Gesture aimed more at invitation than at expression. And, the show’s aesthetic of modesty concretized in its documentation: for posterity, the room receded as the set for a photo shoot.

Riffs on installation views, the photographs that resulted are its official imagery. These were art-directed by Huston-Herterich, and shot by another photographer, Mike Goldby. They feature friends of the artist who ignore the camera as they activate the space with their lazy indifference to its labour.

Presenting the art in use, Goldby’s photographs illustrate the show as its artist intended. Importantly, it was only as art director that Huston-Herterich insisted: she otherwise refused to compromise the agency of visitors by demanding their participation. Only in pictures could she guarantee her vision for the space, and even this vision she outsourced.

Her deliberate deference is made more notable by her experience; Huston-Herterich has documented exhibits in other capacities, and has taught the conventions to others. And, ultimately, Pleasure of a Lazy Laity was about others: it worked as a witty stand against the ego. The artist’s first solo show, it resisted all references to the individual. Its documentation now perpetually inscribes that collaborative ideology, preserving Huston-Herterich’s influence as palpable, but diffuse.

Jimmy Limit

Jimmy Limit is differently evasive in his photographs. His brand is built on genericism; his work draws on the conventions of stock photography, a niche genre that prizes the ambiguous. Like Huston-Herterich’s, Limit’s work exudes whimsy, but his impeccable technique eschews all gesture. He prefers to shoot new objects, before they’ve acquired any meaning, before wear makes them specific or softens what’s striking about them.

Limit’s art mimics commercial photography, and he is a commercial photographer. Besides producing his own work, he shoots for companies and for other artists. Commerce is not, for him, in conflict with creativity. Rather, it’s the logic of the world and the logic of the photo that conflict. Translating between real and pictorial space remains a technical skill, perfected by professionals. Cortázar’s photographer is a translator by trade; so, effectively, is Limit.

His fluency makes him indispensable to other artists: in our post-internet age, art is primarily experienced via online imagery. As an installation photographer, Limit undertakes what Susan Sontag calls the “evangelical incentive” of translation: he works to expose others’ work to a wider audience.

When working for himself, maximum exposure remains – per the stock mentality – Limit’s goal. Consciousness of this end pervades his process: he works with a constant view to the final product – the image. When he makes objects, he sculpts them to appear from a particular angle. And, when he arranges photographs as objects on the wall for his exhibitions, he is anticipating the installation views that he himself will shoot.

He most recently realized this plan with the exhibit Show Room at Clint Roenisch Gallery at the beginning of 2013. The show institutionalized the photographer’s privileging of image over object: at the front of the gallery, Limit displayed his ‘real’ products, his images. He tucked his sculptural work into the back room and, later, photographed it installed. The installation persists in imagery quite close to the artist’s studio work; the gallery walls are only slightly more textured than a typical Limit background. To take these shots was perhaps more to transcribe than to translate; they were designed for the lens. Precisely composed, these views themselves warrant display – and the process could continue infinitely.

Andrea Pinheiro

In Pinheiro’s practice, as in Cortázar’s story, tacking photos to the wall is a gesture of continuance. Photographs can preserve unnoticed details that observers can discover later; attentive audiences can extend the life of a captured moment. Pinheiro sees that truth and raises it: the image on the wall may continue imparting information, and meanwhile persist in recording.

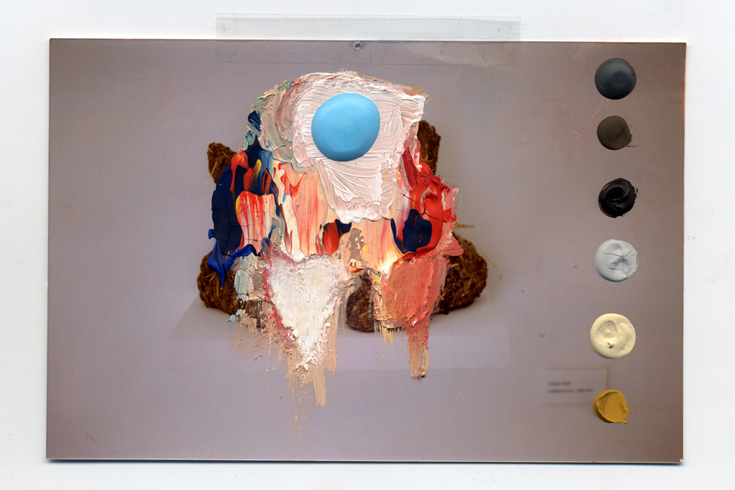

Often thematizing the receptivity of the photograph, Pinheiro’s work links sensitivity to objecthood. Mutability shows up in materiality; texture implies perpetuity. For the series Safn (2010 – ongoing), the artist painted onto pictures she took of the eponymous gallery space. Enlarged from postcard to poster-size, the applied paint reads almost sculptural.

The brushstrokes are explicitly expressionistic, the photographs implicitly so. Both are personal, and to some degree Safn comprises indexical portraits of the artist. The shots are casual; they are Pinheiro’s spontaneous records: unofficial souvenirs of an experience, preserved by the camera. The paint is her response to the prints, recorded by the brush. Both deliberately retain a certain crudeness.

The marks are elicited by the image, and the photos by the space. The space, in turn, is filled with others’ art. Pinheiro paints With Roth, On Fleury, Over Andre and Neuhaus. To this extent, Safn constitutes a series of unauthorized collaborations with iconic artists, anathematic to the traditional installation view.

Moreover, though, the series documents a synergy between audience and exhibit. Safn is a personal collection, housed in a home: effectively, Pinheiro also collaborated with the collectors. Their practices parallel: like collecting, photographing is a way to express through observation and selection. Both group things together in a context, and it’s this gestalt – the whole gallery – that Pinheiro paints with, on and over: zooming out is as important as blowing up.

Heather White is a Toronto-based writer whose current interests skew to the narrative and psychological in contemporary art. She has recently contributed to C Magazine, The Brooklyn Rail, The San Francisco Arts Quarterly and the Telegraph-Journal. Her writing was awarded a prize by the Canadian Art Foundation in 2012.