Steve Reinke reflects on mortality at the Whitney

Memories, fantasy and the body have long been central themes in the work of Chicago-based Canadian Steve Reinke. Perhaps best known for The Hundred Videos, produced between 1989 and 1996, and comprised of 100 films and five hours of non-linear footage, Reinke’s work often confronts the authority of filmmaking and the construction of the documentary genre. He also produces irreverent text-based drawings.

Reinke’s video art can be found in museum collections around the world, including New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the Pompidou Centre in Paris and the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. This year, he is one of three Canadians whose work is featured in the Whitney Biennial. (The others are Paul P. and Ken Lum.) The video presented at the Whitney, Rib Gets in the Way, is narrated in the first person by Reinke, and addresses mortality, the body, the archive, and the embodiment of a life’s work. The longest section of the video presents an animated adaptation of Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophical novel Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883–85). The animations in the video are by Jessie Mott, a visual artist and writer whose work consistently engages a menagerie of human, animal, and celestial forms and with whom Reinke has collaborated several times before.

Here, Reinke speaks with Toronto-based writer and curator John G. Hampton about his inclusion in the Whitney, whether he’d rather have become a philosopher, and Dr. Seuss.

John G. Hampton (JH): How does it feel to be a Canadian exhibited within the context of “the best of the new American art”?

Steve Reinke (SR): I still think of myself as a completely Canadian artist, though I have tenure at an American institution, own property down here and am about to marry an American.

JH: Your tenure at this “American institution”, Northwestern University, is, of course, in art. But, I like to think of most of your work, including Rib Gets in the Way, as being produced by an oversexed philosophy professor who has regressed to a state of childlike wonder and imagination. Have you ever wanted to be a philosopher?

SR: I thought I was a philosopher. Well, perhaps a literary philosopher, an aphorist like Cioran or Nietzsche, or a writer of parables like Kierkegaard.

JH: Well then, speaking as a philosopher, or aphorist, do you think artists make good philosophers?

SR: Probably not so good, but still better than academic philosophers.

JH: One of the differences that might still exist between the artist philosopher and academic philosopher is in the degree of conviction or a belief in objectivity. How much of what you say in your work do you actually believe?

SR: Well, if it’s belief as connected to Truth, I don’t believe any of it. The work is propositional; it proposes certain thoughts, projects points-of-view, desires, affects, opinions, in order to open up possible lines of flight. Belief seems to me largely irrelevant, especially in relation to some kind of transcendent Truth. I’m looking for new ways and things to think, speak, enact and feel.

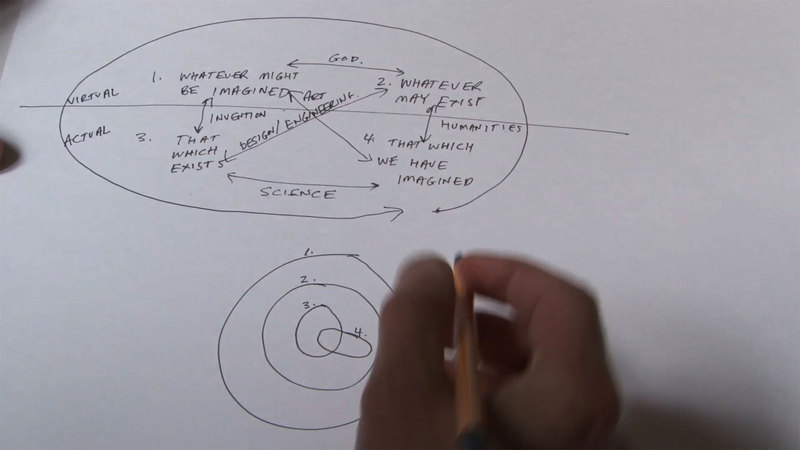

JH: This sounds a bit Deleuzian in the sense that art is what proceeds philosophy by exploring pure thought before it gets tied down to anything so concrete as a belief. Do you think that artistic disciplines are more conducive to this kind of free experimentation in thought than more traditionally written philosophy?

SR: Yes, but it has always been the case that philosophy only becomes interesting when it is also something else: usually poetry, music, science fiction, comedy or autobiography. And, with phenomenology, visual arts can be added to the list.

JH: With the omnipresence of language in your practice, it is tempting to interpret it linguistically, reading it all as a text. But, in most cases this seems a bit backwards. It seems, to me, more effective to look at your text as image rather than the other way around. This may be most clear in your Ruscha-reminiscent text drawings, which you used as introduction option number two in Rib Gets in the Way. Is this a mischaracterization? And, does this privileging of intuition over logic relate to your peculiar brand of philosophical play?

SR: My thesis advisor, Jan Peacock, recently reminded me that she’s said all along that my work is more image-based than I acknowledge. And it’s true: one of the lies I tell myself is that I’m a writer and performer of texts, a monologist, and that these texts are put in relation to images, but the images aren’t mine. But, increasingly, the images are more and more constructed, more and more like animation – often actually cartoons – so it is just not tenable to say they already existed prior to (and separate from) the monologues. Still, it seems to me that images are uncontrollable, mysterious. When I write, I at least have the illusion of control and mastery. I am making meanings directly. Images may be sometimes affectively direct, but tend to be frustratingly indirect linguistically.

My privileging of intuition over logic (or play over argument) does relate to this. I don’t think humans are rational, though it can be funny to pretend we are for a little while. I’m interested in psychoanalysis and surrealism in relation to this: the death drive, etc.

JH: Rib Gets in the Way does seem more “death driven” that the rest of Final Thoughts; was this always the plan? A play on its titular phrase?

SR: Yeah, I like the title Final Thoughts, both because the thoughts are relatively unending – a long stream of material, with the final final thought being final only by virtue of my no longer working, presumably because I’ve died, and thoughts about mortality and other liminal things. Earlier components of the series were more about mortality in the abstract but, in this one, I have a stronger presence. The narrators in my work have become more and more fragmented since Anthology of American Folk Song – not really me or any particular individual/character. But Rib has a fairly straightforward, cohesive narrator. It is the only work of mine, so far, where I deliver monologues on-screen, full face and everything.

JH: Are you consciously crafting a “late work” period in the same way as The Hundred Videos self-consciously delineated your early work?

SR: Yes. Having such a short life is a strange thing.

JH: That is not what I meant! But, you do seem to be ahead of schedule. In Rib Gets in the Way you re-enact a monologue that was first presented in Final Thoughts Series One. In it, the narrator suggests that Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophical novel Thus Spoke Zarathustra is destined to become a children’s novel and, as such, he/you propose to make a cartoon rendition of the novel. In the first performance of this monologue you claimed you would revisit the project as one of the last components of your Final Thoughts series, to be completed in 2040.

SR: From the beginning – the first video of The Hundred Videos – the narrator has put forward certain projects in the first section of a video and then either not done them, or done something completely different in the second half. This failure or gap has been central to the work. When I first performed that monologue, I had no intention of actually doing what I was proposing – an animated version of Thus Spoke Zarathustra for children. In fact, I thought it, if not impossible, ludicrous. For me, it is very satisfying to have proposed – again – something outlandish, but then to have done it in a straightforward manner.

JH: What other philosophical novels are destined to become children’s books? Atlas Shrugged?

SR: In the future, it will go the other way: children’s books will be seen as philosophical works, beginning with Dr. Seuss. This started a little bit with theology and The Gospel According to Peanuts.

JH: Ha! Well, speaking of revising the canon, I loved your proposal to consider the work of Robert Smithson and Robert Mapplethorpe as if it was produced by a single hybrid artist of Roberts, and now I’m expecting an exhibition. If you were to mount an exhibition by this hybrid Smithson/Mapplethorpe, how would you put it together and what would be the ideal venue?

SR: I’d take a small group of leather men to the Yucatan. No mirrors, though, and no displacements. Smithson was clearly anti-vegetation with his rocks and tar pours, while Mapplethorpe at least liked flowers. We’d go half-way and do something with moss and lichen.

JH: Would this be open to the public?

SR: We’d bring back photographs. No sculpture.

JH: If you could meld yourself to one other artist as a hybrid, who would that be?

SR: I’d like to be Raymond Pettibon. When I was younger, I liked the Zen belligerence of John Cage, as well as the amount and range of his work. I think a Sterling Ruby/Steve Reinke hybrid would be great.

JH: Do you think that Biennials like the Whitney’s play an important role in the pre-emptive creation of Art History as archive?

SR: I don’t know. I think it tries to be outside of both Art History and the market. Most of them are a weird combination of famous artists who aren’t necessarily hot at that particular moment and younger artists, many of whom fall straight back into obscurity. This year, there aren’t so many younger artists. The archive is one of the main themes this year, particularly on my floor, which was curated by Anthony Elms.

JH: And, final question: who were you most excited to see in the Whitney this year?

SR: Well, it’s great to have my friend Elijah Burgher be included. And, Jacolby Satterwhite.

Steve Reinke and Jessie Mott’s Rib Gets in the Way appears in the 2014 edition of The Whitney Biennial until June 8.

John G. Hampton is a Curator/Artist from Regina, SK. His recently curated exhibitions include Why Can’t Minimal: an exhibition of humorous minimalism, Coming to Terms: translation and the multiplicities of languages, Sculptural Video: video art beyond the screen, and solo exhibitions by Heather Cassils, Soft Turns, and Richard Ibghy & Marilou Lemmens. He currently lives in Toronto, ON, where he is the Artistic Director of Trinity Square Video and the Curator in Residence at the Justina M. Barnicke Gallery.