The beautiful, lurid, generous and evil work of Balint Zsako

The art of Hungary-born, Hamilton-bred and currently New York-based Balint Zsako is arguably even more compelling than this globe-spanning pedigree. His fantastical open-ended narratives give the viewer the impression that one has been issued a private invitation into lurid daydreams where representations of base fears and fantasies play out at his will.

“When I start a work,” he states, “I don’t know what it’s going to say.” His naïve watercolours, accented with finely drawn black ink details, present us with naked people involved in all manner of survival and vice. He proclaims a fascination with human behavior that inspires him to create a “reflection of a world that is beautiful, ugly, masculine, feminine, generous and evil all at the same time.” In this world, people might share their bodies with machines or spontaneously sprout arterial roots into the earth. Hair sometimes creates unfathomable entanglements or reminds us of occult practices; birds swarm amidst floating guns and people drink, defecate, urinate and procreate.

Zsako’s darkly whimsical practice takes an interesting shift when the artist turns his hand – or more accurately his knife – to the art of collage. It seems as though the technical limitations of the medium – for instance, the practicality of having to find source material – create a structure that has led him to an entirely different artistic approach. According to Zsako:

“The two ways of working are separate. When I work on collages, I don’t think about drawing and vice versa. They both deal with telling open-ended stories, but the labour in constructing collages has a lot to do with looking. You look for many, many hours for the right background or figure for a composition. Then, you try parts out; move them around until they fit. It’s an art-form of editing as opposed to the immediacy of making a line with a brush.”

In his series Audubon’s Birds, begun in 2011, he is in the process of creating a taxonomically correct alternative to John James Audubon’s classic tome Birds in America (1840). Approximately 50 collages away from completion, Zsako re-envisions each of the 435 plates of the original text by integrating each bird into mostly obscure Old Master paintings cut from expired auction catalogues. “In my collages I want to see how the familiar language of Old Master oil painting can be made contemporary by the techniques of collage,” says the artist. Sourcing the Old Master paintings from the catalogues provides Zsako with several advantages. Not only do the glossy pages come cheaper than hard-cover art books that would provide him with a similar picture quality, but often the paintings are less familiar. This enables him to consistently work within the stylistic parameters of the classic genre without being limited conceptually by the stereotypes associated with more famous works.

Early pieces in the series feature birds seamlessly integrated into the paintings. Over time, Zsako has shifted the birds from their primary roles and started to focus on creating bizarre narratives that intentionally defy the conventions of the original paintings. He also pays tribute to the history of the medium by copying various techniques used by collage artists such as Max Ernst, John Stezaker and John Baldessari. This historical exploration of practice creates striking differences between the individual pieces. While some works show the clever and carefully cut image retrofitting typical of Ernst and other photo-montage artists, in other pieces large geometric shapes, including squares or triangles, allow discordant images to be interspersed more haphazardly into the background picture in a style more similar to Stezaker. The stylistic nod which creates this pointed diversity in his collages is one that doesn’t seem to be present within his paintings. Zsako easily names painters he admires, such as Ellsworth Kelly and Joan Mitchell for instance, though any influence on his practice is not readily apparent. “I look at the work of many artists, often ones whose work doesn’t look anything like mine,” he admits. (Zsako’s parents, Istvan Zsako and Anna Torma, by the way, are also accomplished and respected artists in their own right; Zsako has collaborated on exhibitions with both.)

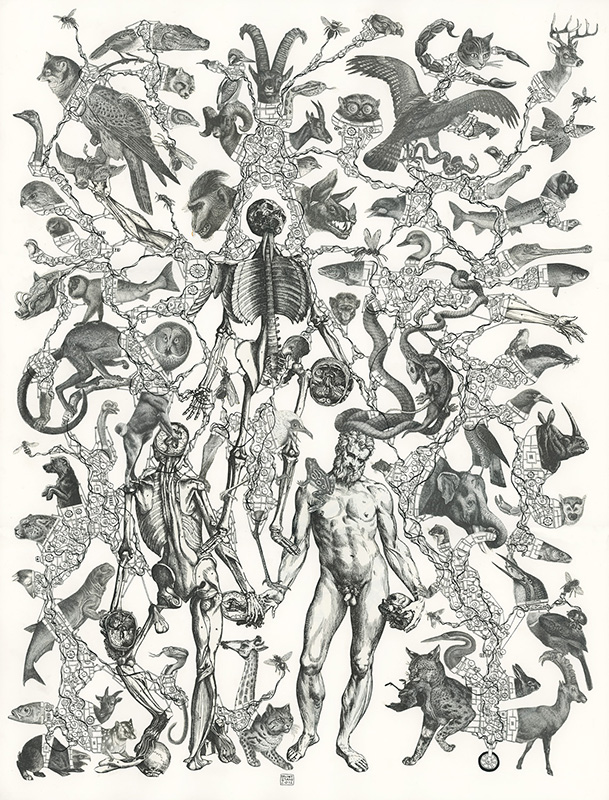

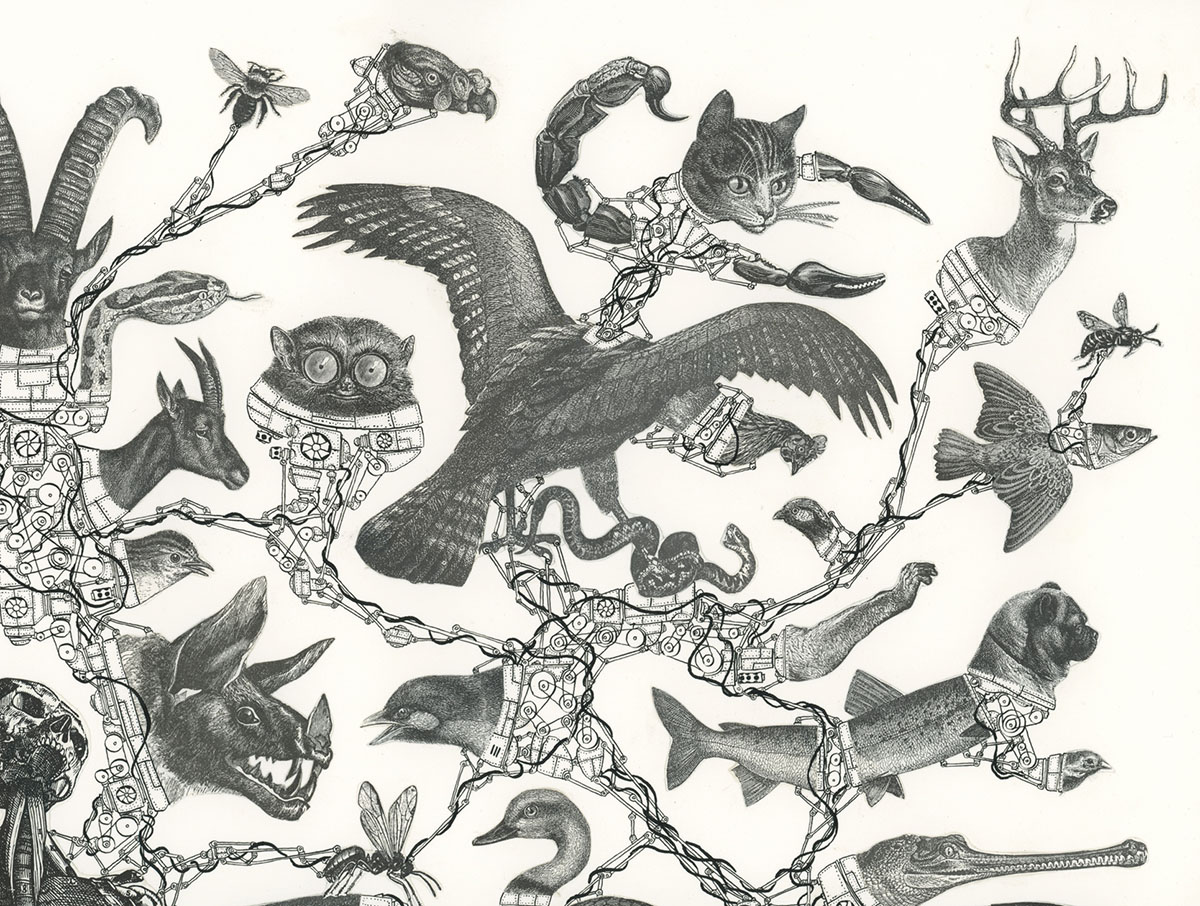

Despite his two completely different modes of process, Zsako forges a convergence between them in Vesalius Machines (2012). Employing a hybrid process he began using in 2003, he combines images collaged from Vesalius’ Icones Anatomicae (1543) with obsessively meandering ink drawings of mechanical parts drawn in his signature style. Devoid of colour, each of his elaborate plates presents the viewer with a baroquely ornamented pictorial spread. Zsako explains, “For these collages I cut out ten times more source material than I need. Then, I play around with the arrangement of printed material until I get a composition that is a good starting point for linking together with drawings of machine parts.”

At first glance, the convoluted mass of lines is reminiscent of a Dutch etching prior to an Ernst-style cut-up. Zsako reveals that the lack of colour is an intentional choice applied to make the work look as though it is all done using the singular technique of engraving. (“I want it to be difficult to tell where the collage ends and my drawing begins,” he says.) Each work in this series of six is organized based on an easily recognizable universal theme. Closer inspection reveals absurd visual mash-ups reminiscent of the fantastic fictions created in the artist’s paintings. Zsako uses the structure afforded by each motif to allow him the same kind of unplanned visual exploration as in his drawings. His concrete daydreams offer stream of consciousness answers to his own questions, such as, “How does a machine compromised of wild animals compare to a war machine or a food machine?”

In his most recent series, Modern Dance, first presented as a solo show at Katharine Mulherin’s booth at Montreal’s Papier 14 art fair earlier this year, Zsako finally gives the viewer the chance to engage in the breed of storytelling that makes his work so provocative. In this series, the artist has created a number of small pieces that fit together interchangeably to create ever-changing horizontal narratives. The idea came to Zsako after the creation of a large piece (60 x 90 inches) executed using nine sheets of paper tiled together and requiring months of labour. “Through learning how to tile a work so the narrative and landscape continue seamlessly, I figured out the technique I used in [Modern Dance],” he says. The project led Zsako to this new way of working, and galvanized his choice to return to working on a smaller scale. “With a large painting, it’s difficult to jeopardize the work already done with something that might not work. It’s not an oil painting, you can’t wipe it off. So I think I found my scale,” he explains. “If I ruin a small work, it’s a couple of days of work gone, not a couple of months, and that freedom leads to interesting results.”

Even as he continues to work on the culmination of this first series of commutable paintings, Zsako muses about future projects he intends to complete in this burgeoning style. His most intriguing proposal includes a set of plates that would be arranged in a grid so that the audience could rearrange the various components of the sky, land and subterranean sequences to shape personalized versions of his twisted narratives. At this point, his modular device is clever while avoiding any sense of gimmick. By allowing spectators to play with his work, Zsako not only gives us the chance to see the world in his way, but teaches us how to look.

Trish Boon is a freelance art writer who has contributed to Canadian Art magazine, and the mother of a three-year-old. She returned to teaching other people’s children in September.