Hito Steyerl's video works find new ways of revealing truths.

Hito Steyerl is a master of a particular type of political satire: one that evinces fantasy and absurdity in the face of the fantastical and absurd aspects of living in an image-laden society. The subjects of her varied and prolific works – lectures, writing, video and installation – range from the presence of arms manufacturers as corporate sponsors of museums, to the causality of both weather and the global financial crisis of 2008, to the relationship between labour and language in contemporary art institutions. Her solutions? Catch a bullet, be water, become unintelligible.

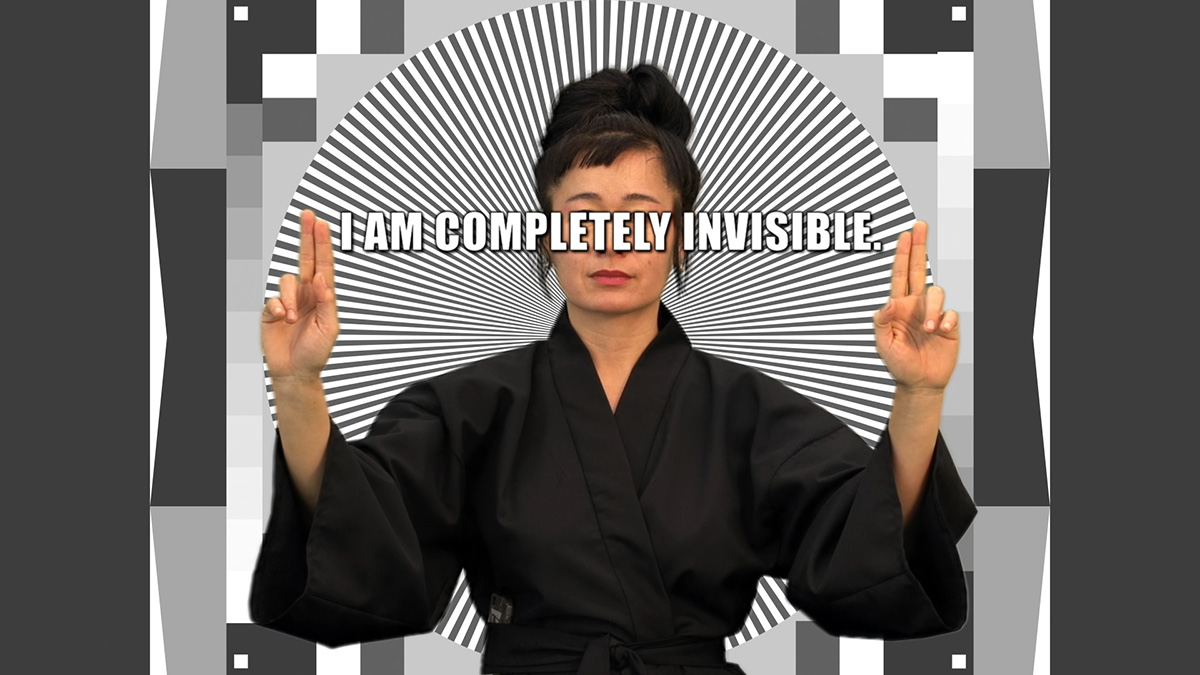

As a finalist for this year’s AIMIA | AGO Photography Prize, Steyerl joins Annette Kelm, Owen Kydd and Dave Jordano in an exhibition at the AGO this fall. Her contribution, How Not to Be Seen, A Fucking Didactic Educational.MOV File (2013), is certainly the least photographic among the bunch, although it is deeply engaged with the ontology of photographs: what the unceasing production and circulation of images, still and moving, means for our political moment.

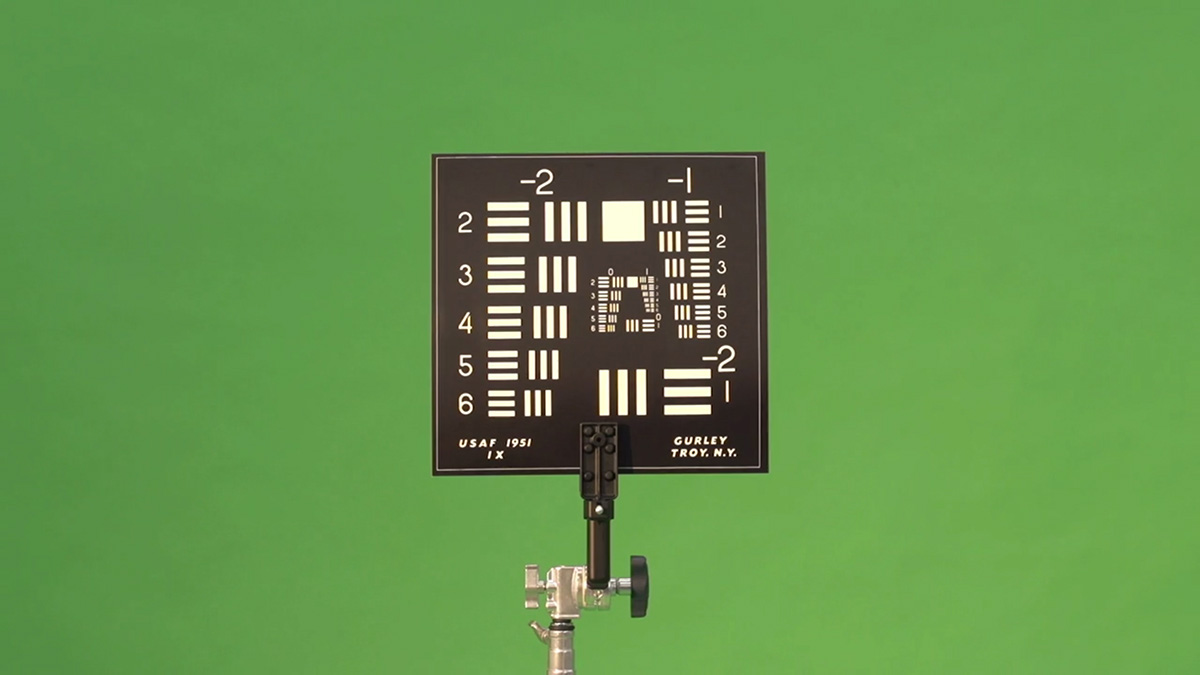

Steyerl’s installation at the AGO structures itself first as a kind of trompe-l’oeil fabrication around a vintage resolution scale — one, she explains, that was used, beginning in the 1950s, to calibrate aerial cameras installed across a stretch of desert or plain. Now, these resolution scales have been replaced by new ones, which more effectively calibrate for pixels. Nonetheless, the floor of the gallery is marked with stretches of white vinyl in imitation of the now-decommissioned resolution scale, conjuring an uneasy possibility of surveillance, even inside the enclosed gallery. Alongside the installation, black bars along the walls reveal themselves as entrances to Steyerl’s video. Like many of her works, How Not to Be Seen sits squarely between satire and seduction, lulling viewers with its soothing British text-to-speech narration and sleek 3D-modelled environments even as it probes the contemporary conditions of mass mutual surveillance: the dual reality of ubiquitous user-produced images and political forced disappearance.

Writer Alison Cooley sat down with Steyerl before the opening of the 2015 AIMIA | AGO Photography Prize exhibition.

Alison Cooley (AC): I have read in other interviews that you’ve given that you don’t necessarily qualify yourself as an artist, first and foremost. I’m wondering, in the space of somewhere like this photography prize, in this institution, what it means to be identified as an artist, or to identify yourself as an artist within this space?

Hito Steyerl (HS): Well, you know, I’m sort of used to being mis-identified as an artist (laughs). It’s nothing new. I’m happy about it because if I had continued to try to be a film maker, then I don’t think I would have an audience whatsoever. So any audience, wherever it is, I’ll go for it!

AC: Speaking of film-making…

HS: (laughing) Maybe I should have been a painter!

AC: There is a thread that runs throughout your work, which is an investigative search —whether that’s the search for the images of you in this bondage porn in Tokyo, or the search for your friend, Andrea Wolf, who disappeared while fighting for the Kurdish Workers’ Party — you’re often doing something that might be done by journalists or documentarians. But, obviously, the relationship to truth in your work is really complicated. When you do that kind of investigative work, how do you conceptualize your responsibility to truth?

HS: I take it really seriously. I really do, even though people don’t really believe me, because I’m lying all the time. (Laughs)

But, you know, I think it’s pretty obvious that I’m fabulating and speculating also because sometimes — oftentimes — it is the only way to tell truth, which otherwise is over-expressed to a point that people are not able to perceive it anymore. It’s also about finding ways to express truth so that people can start listening to them again, and sometimes the only way to do that is fiction. But, I do feel a strong responsibility towards truth.

AC: It seems like this fiction is very present in this work at the AGO, How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File, which provides instructions on how to embody something impossible. I’m wondering how you imagine people applying those instructions?

HS: I don’t know! (laughs) Try it. Go ahead, it will be fun.

AC: In other recent installations of yours such as Liquidity Inc. (2014) and Factory of the Sun (2015), you’ve created this immersive space, and you’ve implicitly invited people to spend some time with your work. You’ve written about the relationship between video in the museum space, and spectatorship in the cinema in Is a Museum a Factory? Are you trying to rescue something of the theatre and bring it into the museum space?

HS: Maybe… yes, probably. But, I think one has to do it differently for many, many reasons. One being that, first of all, I think you should provide wifi access so people can have time to check their emails, while they’re watching the phone. That’s the first priority!

It’s really nice. Not so much in film theatres, but definitely during lectures, I see peoples’ faces lit up by their smart-phone screens. It’s nice. That’s how spectatorship works now.

It always expands, you know. The physical space itself is important, but it always expands onto the other platforms at the same time.

AC: You’ve also made the claim that the Internet has moved offline and into our reality. Of course, we still have a divide, and when we think about the politics of the circulation of images, I’m wondering, how do we start to approach an ethics of being online?

HS: That’s a vast question.

AC: Maybe the better question is, how should we be using the Internet?

HS: By rebuilding it, I guess. I think that’s the only way, essentially, at the end of the day. Otherwise, just use it for what it works for.

By rebuilding it I mean, at the moment, it’s in the service of a few mega-corporations and governmental or post-governmental institutions, so in that sense, it’s a hugely controlled space. So, if people want it to be any more interesting than it is now, we have to rebuild it somehow.

AC: You’re often very much in your work, especially in lectures. But also that you don’t shy away from speaking about personal experiences. You somehow avoid some of the ghettoization that many women artists face, where their works are conceived as only being about the body or the personal. How do you do that?

HS: I had to face so much ghettoization from the beginning, from being a non-white artist in Europe. I’m very used to dealing with that. So, I gained some experience in trying to absolutely refuse these kinds of compartmentalizations.

AC: By distancing yourself?

HS: No, no. What do you mean by a distance? No, no. I put myself in it. Maybe not in an entirely expected way.

AC: I guess when I say distance, I mean a kind of emotional distance.

HS: Yes, of course. I mean, it’s not me. It’s an image. It’s a version. It’s something. It’s raw material. I don’t take my image that seriously.

AC: You talk about the way that the image obscures its own production, especially now — I wonder, though, if it’s not always been the case that we have to skeptical of the image’s constructedness?

HS: Of course. You know, this is because of my background in film and documentary. If I was an architect, for example — someone who draws maps or plans — it would be completely obvious. If I did something related to religious images, then it would be completely obvious that these are actions and interventions. It’s just the bias that comes with photography and lens-based image production. It’s just a tiny part of image production. But, of course, it’s always been like that.

But now, lens-based media are being drawn into that. They used to be seen as being purely representative, but not generative. Now they are very much generative.

AC: And is that generative capacity because of the Internet, and because there are so many of them? What changed?

HS: I don’t know. Circulation is definitely a factor in this. How this exactly changed, I really don’t know. But, it’s been noted by so many people. In the 1980s, somehow the causality in representation changed… that images were seen as a model that one would have to imitate rather than as records of something that happened already. Something has changed. I don’t know why.

I also think the opportunities for co-creating images, and also publishing anything, have increased a lot. People, who are nowadays called ‘prosumers’, they used to be seen as recipients, not as co-creators. Not as… well… not as participants in something that has turned into a real mass image production.

Anyone can do it. We all have some capacity — the capacity to increase the noise by perpetual image-making!

AC: Maybe that’s how I’ll become invisible.

HS: Yeah, absolutely.

Alison Cooley is a writer, curator, and educator based in Toronto. Her work deals with the intersection of natural history and visual culture, socially engaged artistic practice, craft histories, and experiential modes of art criticism. She is the 2014 co-recipient of the Middlebrook Prize for Young Curators, and her critical writing has appeared in FUSE, Canadian Art and KAPSULA, among others. She is also the host and producer of What It Looks Like, a podcast about art in Canada.