Intimacy and race in the art and writing of Hannah Black

“As people who are not cis white men we have to try to take art as an institution approximately as seriously as it takes us, which is not very.” – Hannah Black

“The Loves of Others” was the first piece of Hannah Black’s that I read. Her observation that the couple “bears all the insufficiencies of present societal relations” was like a salve. I was in Brussels, nursing heartbreak inflicted by a handsome Dane whose white masculinity nearly erased my whole being. After perfectly describing cis het romantic love, Hannah moved on to the scary depth of it, the loss of self that can happen. Her essay succinctly articulated something I had not yet found: she talked about the effects of capitalism in a way that incorporated race and class and gender. Hannah writes beautiful texts, and she also makes videos and sometimes does performance. Since that first piece, I’ve watched Hannah’s videos online, and read her writing in Rhizome, Art in America, Frieze and Artforum. A few months ago, she published her first book, Dark Pool Party. Still, a lot of her videos and writing are dispersed and difficult to find. Whenever I do encounter Hannah’s thinking, I am comforted that she is doing the difficult work she does within the confines of the art world. I feel as if her art practice activates a shared vulnerability that transforms into strength. To do justice to this intimacy requires that it be written about in a personal way, which is what I will try to do here.

In “Closing the Loop”, Aria Dean points out the near absence, in art history, of “black women looking straight at themselves and making that looking public.” For me, this rarity is one of the strength of Hannah’s work. Departing from the notion that “the body is a register of more or less obscure credits and debts, worn as alterations on the surface, as turbulence in the organs, weighed in bone,” Hannah interrogates what it means to be bodied. She uses everything at her disposal: language, experience, personal history; tuition in literature, film, art writing and studio practice. The thought that “there is no intercessory form of being, neither in art nor in life,” leads Hannah to call out the insufficiency of analogy. Though language is a muscle that runs through her work, she challenges herself by resisting to settle for its technical limitations: “[S]he goes on to the next line and the next, hoping every time to discover new material to barricade, against hostile elements, the collective practice of living”.

The text “Atlantis,” for example, begins with an exploration of the contradictions of being gendered and racialized in the shared space of a gym. In a weight room, Hannah observes simultaneously not existing and becoming “more and more existent” at the same time. Here, as in other works, she takes stock of her experience of hypervisibility and invisibility, of being gendered and raced, all the while sitting these observations within the interstice of a specifically classed position. Hannah embraces and attempts to articulate the complexity of her existence, in which her “ancestral ghosts, [include] the illiterate shtetl Jews and field negroes and even the remote Irish peasants.”1 As a black woman critical thinker, I have to make a deliberate effort to circumvent a particular form of white, male western bourgeois intellectual thought that emerges from a presumption of neutrality. I am careful to complement the impressions they offer with what might have been disregarded or overlooked. Surveillance scholar Simone Brown has perfected this method. An apt example is her discussion of the enslaved women, seeing but unseen, sitting under the floor planks of a ship carrying Panopticon inventor Jeremy Bentham from Smyrna to Constantinople in her book Dark Matters. One of Hannah’s gifts is the ability to evoke similar insights and critical perspectives. Her work, her presence, her generosity of self and way of seeing has given me, as a black thinker, a kind of permission to be more than marginal outside observer to the machinations of the ‘global dominance of whiteness.’ By putting her experience at the center, Hannah makes space on a stage for complex identities to articulate and see themselves. And, as she writes, “As long as they keep their hands off your neck it’s easy to breathe and walk around”.

“A lot of the work that I come across is by white men—some work I like, some I don’t, but certainly a lot of it. As a result, I know a lot about what that experience of the world is like, perhaps more than I even know about my own experience.” – Hannah Black

This spring Hannah and some friends came to housesit in the farmlands of central France. We took turns cooking decadent meals and walking Rosa the dog. One late night, Hannah and I ended up in front of the computer playing an ADD version of show and tell. We talked about The Many Headed Hydra and Lil’ Wayne and Sylvia Wynter. We drank wine and smoked cigarettes by the door, careful not to let the dog escape into the dark fields. Then she pulled up Fred Moten’s poem there is religious tattooing from the Poetry Foundation website and we listened to the link of him reading it several times and tripped out on his lines.

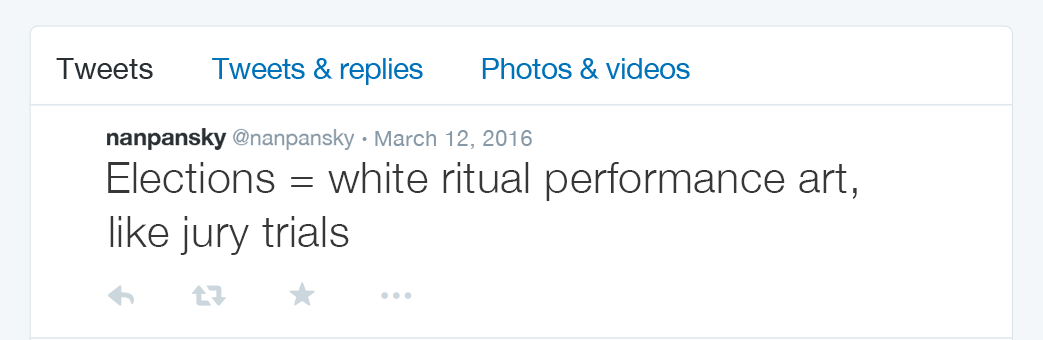

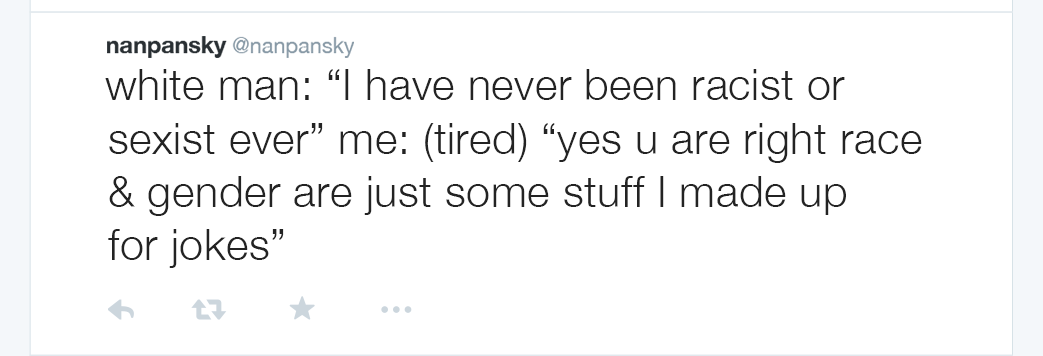

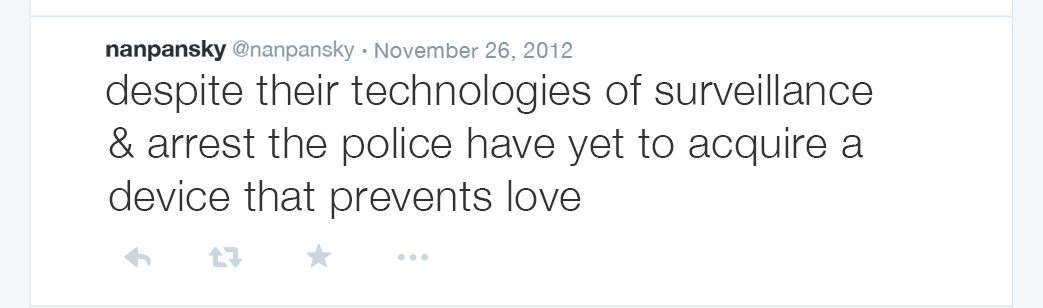

Moten’s poem is graceful, it moves in time through water, cotton and flesh, subjugation and salvation. It captures the contradictory space (skin) created by legacies of imperialism. Blackness has been snugly folded into racial capitalism but in Moten’s words it unfurls and knows itself. I feel a similar thrill when I read Hannah’s words. “The feeling of not being able to read yourself is a dark pool and this is a dark pool party,” she writes. The dancing beauty of her writing sometimes alights on what I feel but cannot express, what I have seen but had no language to understand. Her Twitter especially is an alchemy of woke discernment, quotidian anxiety and shade in just the right cadence to soothe anyone fatigued by society’s insistent denials of its own complicated histories.

“I don’t see how any official politics can be any more important than the intensity of listening to music.” – Hannah Black

At the same farmhouse in France, we played one of those psychology games that generates a personal assessment based on a scenario created from a series of questions like: You’re in the woods (what kind are they?); you see an animal (what is it?) etc. The last question asked us to describe a body of water, and how we would cross it if we had to. I saw a massive, clear lake at the foot of a distant mountain. Hannah imagined an ocean. To me, getting to the other side seemed a pretty straightforward endeavor that wouldn’t even require me getting wet: I would trek around it. Hannah decided she would look for a village on the shore and find people to help her build something on which she might passably sail out to sea. Depending on the version of this game you adhere to, the water represents your capacity for love or your desire for intimacy. How you undertake to cross reflects how you face your emotions. “I sometimes think that my work is a way of expanding my possibilities of intimacy with others, but maybe that’s also just a way of saying that intimacy can be really hard,” Hannah once said in an interview.2 She isn’t afraid to ask for help, and to push through and hope for the best in even the most perilous circumstances.

For a very long time, its seemed unadvisable to me to fully emotionally engage others, it is perhaps a fear of the unavoidable, and possibly painful, truth brought by intimacy in a society afflicted by white supremacy and heteropatriarchy. Hannah doesn’t seam to let such fears stop her. Her work commands space in the world in a particular way, and in so doing disarms some of its inherent wickedness. I am learning from Hannah’s daring, considering what it might be like to risk entering into the body of water. I keep her words in mind: “Anyone can step over the high-tight line of the self and become more than the sum of previous violence, but not alone: circumstance has to rescue us, i.e. other people”.

Sources and Further Reading:

Black, Hannah. The Loves of Others, The New Inquiry, June 2014.

Black, Hannah. Dark Pool Party. Canada: Arcadia Missa and Dominica, 2016.

Browne, Simone. Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015.

Dean, Aria. Closing the Loop, The New Inquiry, March 2016.

Quote sources:

-

Black, Hannah. Passion Oasis, The Princeton Review, May 2016.

- Darling, Jesse. Artist Profile: Hannah Black. New York, www.rhizome.org

All other quotes from Dark Pool Party.

Hannah Black will be appearing as part of the PLATFORM speaker series at Art Toronto at 6:00 p.m. on Friday, October 29. Her talk is presented by Art Metropole and C Magazine in conjunction with the /edition Art Book Fair

Yaniya Lee is a writer and interviewer based in Toronto.