Staging the work of Christopher D'Arcangelo

There were some things I knew before I went to visit Anarchism Without Adjectives: On the Work of Christopher D’Arcangelo, 1975-1979 at Concordia’s Leonard and Bina Ellen Gallery. I had first heard of Christopher D’Arcangelo as an undergrad, when a professor assigned Thomas Crow’s article on “Unwritten Histories of Conceptual Art.” I knew that D’Arcangelo’s work was a form of conceptual art and institutional critique, and that it often consisted of clandestine acts within museums – building walls, moving paintings – related to his work as an art installer and carpenter. His work was a politicized gesture, designating the labour that supports art institutions as art in itself. Because it left so few traces and documents, I also knew that his work has often been absent from historical discussions of conceptual art. Furthermore, I knew that D’Arcangelo died young, and that his marginality and early death are often associated with the terminal radicality of his practice – the idea that he could go no further. Like Bas Jan Ader, he has come to stand as a tragic, even Romantic, icon of the failure (or at least pyrrhic victory) of the neo-avantgarde in the 1960s and 70s.

With this in mind, I expected that any exhibition that aimed to be a retrospective of D’Arcangelo’s work would be difficult: difficult to stage for the curators and difficult to parse for the viewer. The artist would not be present. There would be no performance. It was unlikely that there would even be many photographs of his actions since the bulk of what he left to history were printed statements issued in catalogs or, sometimes, not even that. So, an exhibition about D’Arcangelo would have to be, in part, a reconstruction. Like a crime scene, it would require the assembly of scant and circumstantial evidence. It would require the testimony of witnesses and interested parties. Some element of re-enactment could prove useful. Above all, remaining faithful to D’Arcangelo’s legacy would mean that there could be no easy answers, no straightforward presentation. This is the paradox of his work and what makes it such an effective symbol for Left melancholy in general: that an emissary of radical, egalitarian ideals should at the same time be so prohibitively inaccessible.

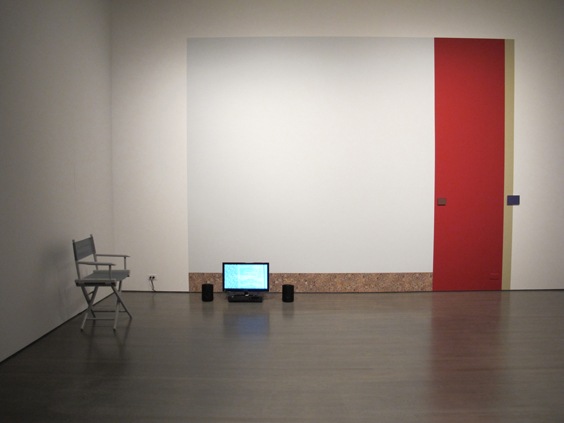

Simply put, Anarchism Without Adjectives curators Dean Inkster and Sébastien Pluot (in collaboration with Michèle Thériault) exceeded expectations. On passing through the doors, I found the gallery’s main hall occupied by three tables, each with two video monitors and four sets of headphones. This is just the viewer’s first opportunity to take in some of the nine hours of video included in the exhibition. I had less than two hours, so I resolved to explore the layout of the show before sitting down to watch the video content. I quickly realized that, in addition to numerous other videos, which include interviews, lectures, staged dramas, and projected text, to say nothing of the wall paintings and the metal structube system, the show also contains a lot of reading material. Various walls were covered with scans of book jackets and interiors, and with posters and ephemera; there were photocopied pamphlets and books; many of the videos also featured books being handled, read or given away. It soon becomes clear that this is less like an exhibition in the usual sense and more like a research library – fitting, since the show was made possible by the donation of D’Arcangelo’s personal archives (previously in the possession of his family) to the Fales library and special collections at NYU. As artist Ben Kinmont points out in a video interview, it was, ironically, the co-option of anti-institutional art practices in the 1970s, and their re-absorption back into institutions, that made it possible to preserve their actions and write their history.

What may not be immediately clear to the viewer is that none of the material on view actually represented works or actions by D’Arcangelo. Rather, the videos, books and objects were projects by ten different artists (some produced earlier and some created for this exhibit) that accompany video interviews conducted by the curators. Altogether, they compose a kind of portrait of D’Arcangelo that materializes through his influence and the traces he left on the historical record. Of the artistic projects, Silvia Kolbowski’s An Inadequate History of Conceptual Art (1998-99) is perhaps the most appropriate. The artist sent letters to 60 artists (40 of whom responded), asking them to be filmed while describing a work of conceptual art that they personally witnessed between 1965 and 1975. In the video, no faces are visible and the camera focuses on the gesturing hands of the participants. Additionally, none of the participants were allowed to identify themselves, or the titles or artists behind the works they describe. I suspect that Kolbowski’s project may have been a partial inspiration for Anarchism Without Adjectives since one channel of the curators’ video interviews is devoted to the hand gestures of the speakers. (Plus, the artist project by Sophie Bélair Clément similarly focuses on the hands of an unseen narrator.)

Kolbowski’s work also raises questions that this exhibition expands upon: who is allowed to narrate history and what are the conditions of its entrance into institutions and archives? And, who has access to his material? Kolbowski’s model of anecdotal evidence and personal recollection allows for multiple – sometimes conflicting – perspectives, and asks the viewer to put in enough time and commitment to build up a picture from fragments. In other words, it’s an approach that calls upon the visitor to invest in developing a personal relationship with the history in question.

Nicole van Harkamp’s Yours In Solidarity (2013) is another multilayered project that offers an indirect tribute to D’Arcangelo’s professed anarchism. The piece is constructed from a collection of letters traded between a large network of anarchists over the course of the 90s. From this material, the artist recruited actors and developed a script to stage an imagined meeting of the international correspondents. The resulting video (realized with remarkably high production values) is displayed alongside a two-channel slideshow of the script and 80 framed notes, adding many more voices (included some impassioned and less-academic ones) to the exhibition’s general polyphony. It’s also notable that Kolbowski and Van Harskamp’s works are some of the only artist contributions to be identified by labels and explanatory wall texts – this marks them as significant keys to the rest of the show but also demonstrates the diversity of framing techniques used throughout, some didactic and traditional, others more associative and eccentric.

The Leonard and Bina Ellen Gallery’s hosting of such a demanding and didactic exhibition is no surprise. It occupied the same building as Concordia University’s library and its principal audience is students. A show like Anarchism Without Adjectives seems tailor-made for visits by seminar classes and, judging by the number of visitors I noticed with notebooks and pens in hand, many people were brought there by an assignment. The interviews with Benjamin Buchloh, Daniel Buren and Lawrence Weiner alone could constitute a masterclass in the legacy of critical art, and the gallery is happy to provide the material for an education. In addition to the artist’s works on display, the amount of information about D’Arcangelo and his context that was “available at the front desk” bordered on staggering.

As a university gallery, the Ellen also has an impressive history of investigating its own institutional conditions: see previous exhibitions like Interactions (2012) and Documentary Protocols 1967-75 (2007-8). Anarchism Without Adjectives is an admirable addition to this history, though some viewers might be puzzled by the lack of reference to Quebec’s recent student protests in which anarchists played a large part. In this sense, Anarchism Without Adjectives was disappointingly of a piece with the generally lukewarm participation of Anglophone universities in the Printemps Erable and of the particularly inhospitable response of Concordia’s administration. On the other hand, there are limits to how obvious and inflammatory one can be when working inside an institution. What a show like this demonstrated, perhaps, is that an archive can be where history is revived or where it goes to die, or both at different times. It only awaits the right user, the right moment.

The exhibition Anarchism With Adjectives appeared at the Leonard and Bina Ellen Gallery in Montreal from September 4 to October 26, 2013.

Saelan Twerdy is a Montreal-based freelance writer and a doctoral student in Art History at McGill University. His writing has appeared in Canadian Art, Border Crossings, C magazine, Bad Day, Blackflash, and The New Inquiry. He has a tumblr at towerofsleep.tumblr.com.

Anarchism Without Adjectives Christopher D'Arcangelo Leonard and Bina Ellen Gallery Montreal Nicole van Harkamp Silvia Kolbowski